It’s been two months since we first heard news of WNBA star Brittney Griner’s arrest and detainment in Russia and since then, any insights into her wellbeing, the case and urgency for her return to the U.S. have been sporadic. For Russia, a country that deals in disinformation and wields intelligence as a means of control, that’s by design.

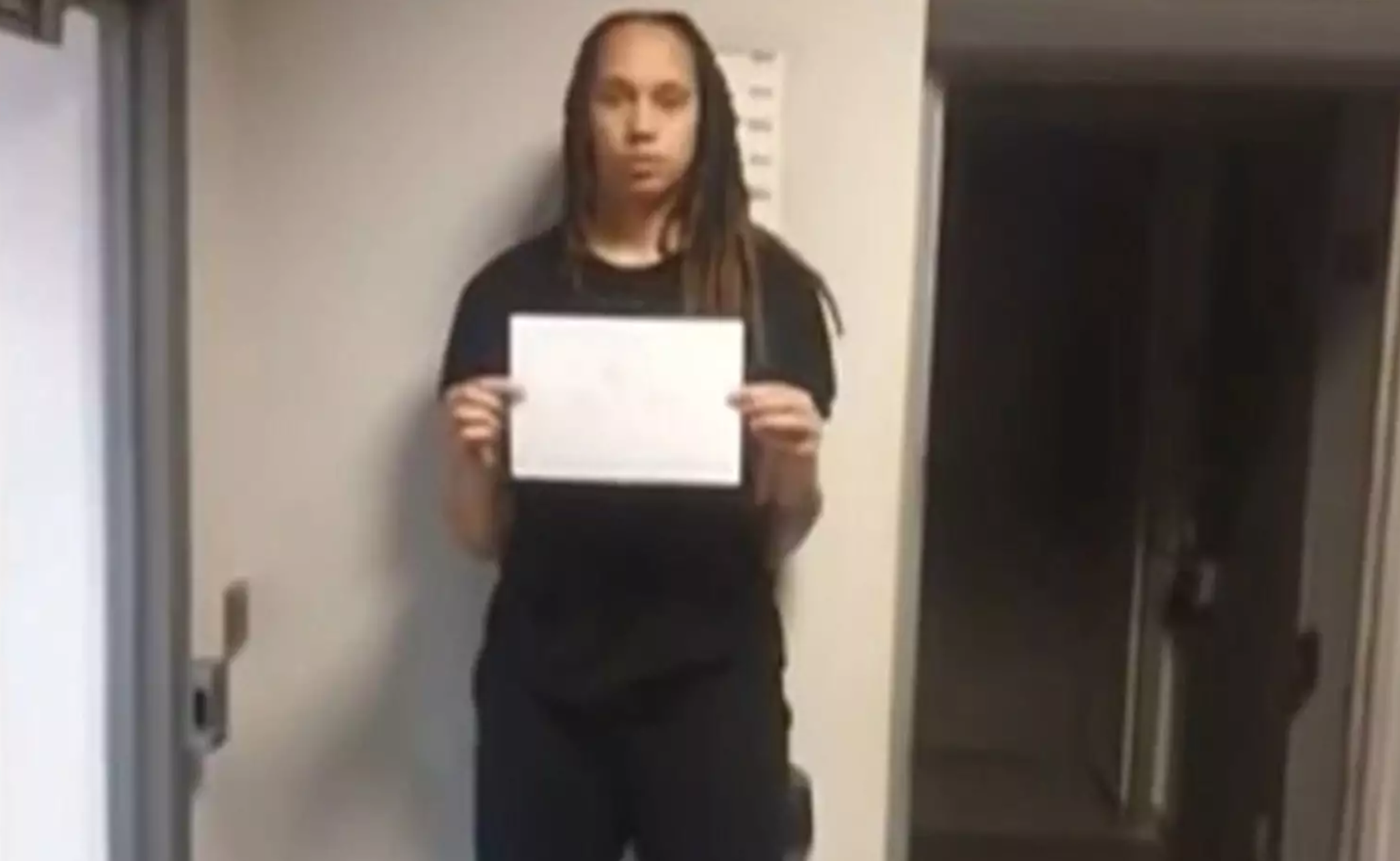

The exact date of Griner’s arrest at Moscow airport can’t be confirmed; the CCTV footage of her moving through security and agents searching her luggage is clipped; a still of her headshot being taken in a Russian police station wasn’t aired on the country’s state television until March 5. There’s no sense of a real timeline to trace for clues.

For Griner, and for the majority of WNBA athletes who head overseas during their offseason from the league, the chronology and reasons behind how something like this happens become clearer in the why of it. The necessity of being away from home in the first place.

Roughly half of WNBA players spend their “summers” playing overseas, primarily in Europe and Asia, to supplement their professional salaries. Any pro sports career offers a short window for success, and athletes, even those that are the highest paid, augment that time however they can. For players in the W, generally encouraged to seek out offseason gigs by the league itself, the difference in income earned from playing abroad isn’t a question of a few additional thousands of dollars, but millions.

Diana Taurasi, a 3x WNBA Champion, 5x Olympic gold medallist, and a storied legend in the sport of basketball, period, earned $1.5 million for just one season with UMMC Ekaterinburg (the same team Griner plays for) in 2015. By comparison, her salary from the Phoenix Mercury was $107,000.

The discrepancy was so substantial that Taurasi opted out of playing the 2015 season for the Mercury, deciding instead to commit to her Russian club for the year. Sue Bird, another WNBA superstar, reportedly earned four times her annual league salary of $93,000 when she played for the Moscow-based team Spartak. Griner, too, earned $600,000 for a four-month contract with the WCBA team, Zhejiang Golden Bulls, at the end of her rookie season — 12 times what she made with the Mercury.

Out of the league’s 144 players, 70 of them committed to alternate teams following the 2021 season.

Reasons for the glaring salary differences between WNBA players and, say, NBA players, are myriad, partially rooted in revenue and broadcast contracts as much as in the generated pay-gaps prevalent in all professional fields.

An average NBA salary is $5.4 million, while the average WNBA salary currently hovers around $120,600.

For contrast, the rookie contract of the NBA’s number one draft pick this past season, Cade Cunningham, was $45.6 million over four years, while recent number one WNBA pick, Ryne Howard, will earn $226,668 over three years. The WNBA’s rookie pay scale is determined by its most recent collective bargaining agreement — a minimum salary for athletes under two years in the league is $60,471, three or more years, and the minimum shifts to $72,141 — while the NBA has no such limits in place.

But then, NBA rookies have been out-earning their WNBA counterparts since the W’s inception. There’s no need for a minimum safeguard when the maximum threshold is still more than an athlete in the WNBA might earn throughout their entire career.

A smaller audience has long been touted as proof of a relative lack of interest in the women’s game versus men’s, and thus a lack of revenue, but then women’s sports have historically not been prioritized in prime-time broadcast windows nor given the same influx of marketing dollars or endorsements by big-ticket sports partner brands.

The problem has never been a lack of interest but a baseless repetition, almost like a self-fulfilling curse, in the claim of it. The proof of this has been the ready and eager uptake of the women’s game across new media and non-traditional broadcast platforms, where the communities that have always rallied around WNBA markets and their players are given new avenues of connection. Turns out if you don’t build it, WNBA fans will.

These direct means of access have also helped the athletes themselves when it comes to self-promotion, partnerships, and connecting fans to their own stories. Modern athletes have a platform and a two-way window which in turn has helped to bring long-ignored inequities to light.

The glaring differences in the men’s and women’s NCAA facilities in 2021’s March Madness tournament started a firestorm across social media that led to the women’s tournament, for the first time, being allowed to use the term “March Madness” in its branding and marketing in 2022. The national women’s soccer team won a settlement with U.S. soccer for $22 million in back pay through the efforts of former and current athletes, which was widely amplified across social platforms.

The proliferation of a unified bold, intelligent, loud, and hyper socially-tuned voice in women’s sports in recent years is also why the relative silence around Griner’s case, and from Griner herself, feels so comparatively cavernous.

Initially, the message heard from Griner’s colleagues around the WNBA and official government channels were to tread lightly and quietly. Griner, a 7x All-Star and 2x WNBA champion, has played for UMMC Ekaterinburg since 2014 and won back-to-back titles for the franchise in 2014-2015 and 2015-2017 alongside Taurasi. She’s a known and supported athlete to the fervent fans of the game in Moscow, and across Russia, which makes the timing and circumstances around her detainment all the more troubling.

With the war between Russia and Ukraine in its early stages, the decision by Russia to arrest and detain Griner seemed a direct response to the sanctions being leveled against Russia. Specifically, those that were placed on oligarchs like Iskander Makhmudov, the Uzbek-born owner of Griner’s team, UMMC Ekaterinburg.

Since Griner’s arrest, justified criticisms have been raised concerning the lack of urgency in advocating for her release compared to if instead, it had been LeBron James or another elite male athlete in her place. While negotiations and any progress won’t be made public, criticisms that the volume of news stories and discussion, even fan-led initiatives, would be far greater if Griner weren’t a Black, gay woman are apt. Public pressure and continued attention to her case could force pressure on the U.S. government to not let up.

At the moment Griner’s case is being handled by Consular Affairs, an entity responsible for ensuring her health via access to regular visits, happening twice per week. But Consular Affairs is an intermediary, not an arm with the power to extract hostages.

On a recent segment of Al Jazeera’s ‘The Stream’, Danielle Gilbert, a military strategies professor at the U.S. Airforce Academy and a fellow at West Point’s Modern War Institute noted that for Griner’s case to be elevated to the next “diplomatic level” it would need to be taken on by the Special Presidential Envoy for Hostage Affairs – a branch within the State Department. If it were, that would mean a presidential sign-off to do whatever it took to free Griner.

Recent appearances by some big names in the WNBA to talk about Griner, like Lisa Leslie on the ‘I Am An Athlete’ podcast and Nneka Ogwumike on Good Morning America, have been heartening. Leslie noted the initial messaging that indirectly spread throughout the WNBA’s circles not to “make a big fuss” about Griner, admitting it was “heartbreaking” not knowing if it was the right thing to do or not.

When asked if she saw the root of Griner being abroad as a gender issue, Ogwumike replied, “When is it not? The reality is that she’s over there because of a gender issue — pay inequity.”

With Griner, there will be no clarity from Russia, and holding out hope for it is as antiquated an impulse as considering women’s sports, and the athletes who undertake them, as secondary. Though her name was mentioned many times during the WNBA’s recent Draft broadcast, and it was announced that she would not be suspended for the current season and would receive her full pay, explicit calls to action from league Commissioner Cathy Engelbert were absent.

Even when those calls do come, there’s a hypocritical tinge. That there’s a time and a place to advocate for the well-being of women instead of that occasion being always, and loudly. That the most direct instances of questioning and speaking out on Griner’s behalf have been from current and former players is testament that the weight of advocacy in and for women’s sports, and for the women in those sports, still needs to come from the women themselves.

WNba Athletes don’t get paid because American women don’t watch WNba basketball.

Dumb bitches are lucky they get paid anything at all. NOBODY watches that garbage product.