Some things just go together. Butter and popcorn. Bryant and O’Neal. Outkast.

So it was, one summer in Austin, with duos on the brain—and enjoying tacos and Tecates—that I lobbed another “if-we-owned-a-movie-theatre” idea to Masseo and Sasha: the double feature. It’s a simple idea. Pair two movies that are better off with each other; movies that form a kind of cinematic couplet. It’s not a new idea. Movie houses have always billed flicks back to back. But there is a lot of fun to be had in finding the rhyme, in finding the echoes across films.

[Sasha also wrote about the inception of this idea but thought the story took place in winter years before he moved to Austin.]

The three of us have been kicking around pairings for a while now. I thought it might be fun to do a little duo review.

So, for this inaugural MMH Double Feature Review, I want to spotlight the two movies that got me thinking about how films can rhyme. No, we’re not talking about A New Hope and The Force Awakens. We’re starting heavy. We’re walking straight into the fog of movie-making, where the line between truth and fiction, documentary and drama blurs.

Sounds complicated, no?

Stories usually are, especially as they get closer to the truth. I’ll offer a little structure to help cut through the complication. I’ll talk about each film in turn, sketching their plots and highlighting some of their cinematic accomplishments. Then, I’ll try to find the through-line for these two works, pull on the stitches that bind them together.

Before we do all that, though, let’s ground ourselves in a question, something to whet the appetite for the hearty serving of docu-fiction that I’ve ordered up. The best question for this duo is super simple: what is the relation between film and reality?

F for Fake (1973, Dirs. Orson Welles & François Reichenbach)

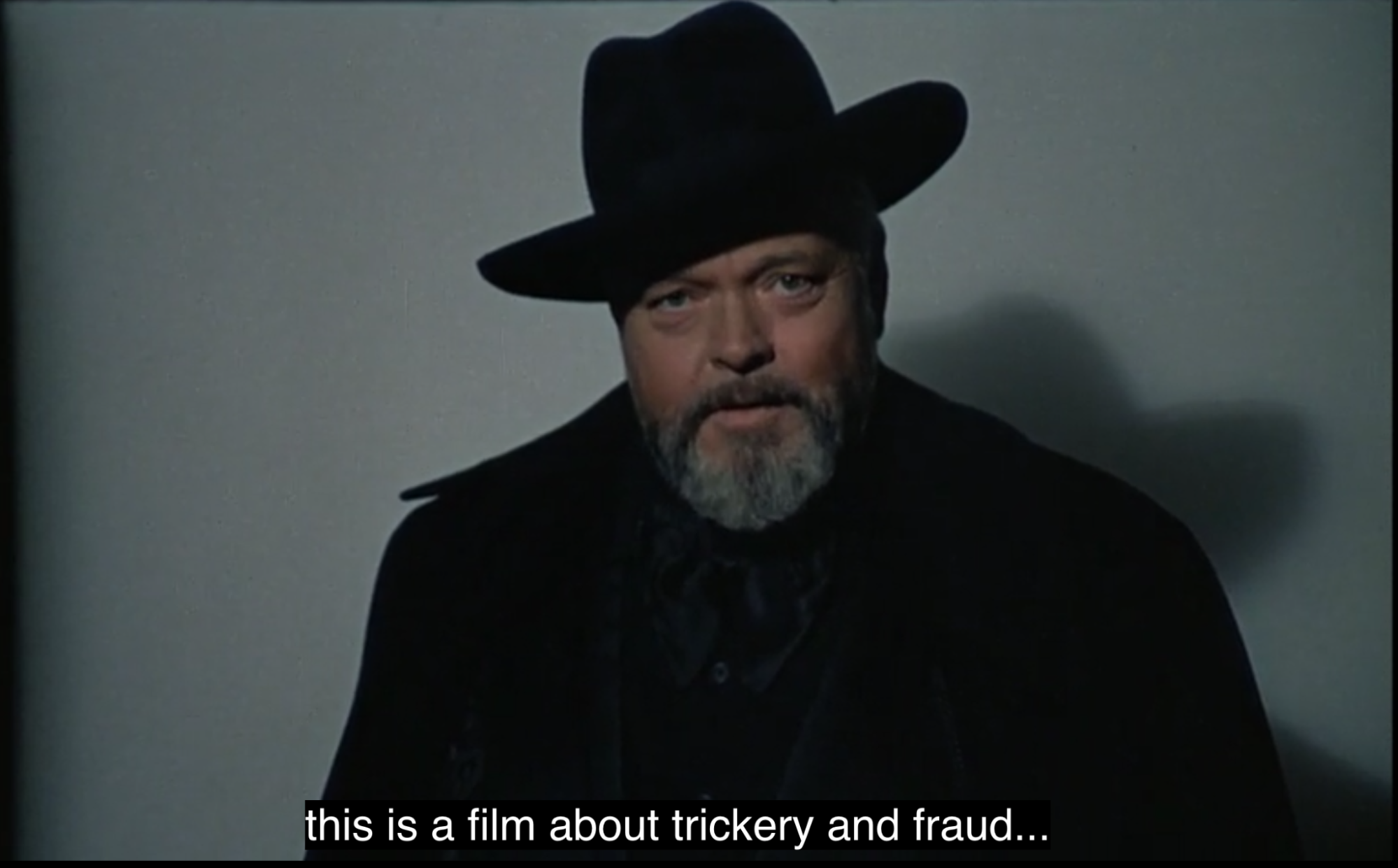

Welles’ first film to reach the screen with an original script is a bit of a shell game, but at least he’s honest about it. Early in his narration, he tells us, “this is a film about trickery and fraud, about lies…During the next hour, everything you’ll hear from us is really true and based on solid fact”. So, he shows us the ball, then he starts the shuffle.

The first shell pushed towards us is the story of Elmyr de Hory, a Hungarian-born painter and art forger who can pull off framable riffs on Matisse, Picasso, and others. “I don’t feel bad for Modigliani,” he says, winkingly, about one of his creations, “I feel good for me.” He’s slick too, shifting focus from his forgeries to questioning the nature of authenticity.

Some true things are told in F for Fake

Should we fault de Hory? Or an art market that commodifies authorship and puts so much trust in the hands of art experts? Experts who, according to de Hory and his biographer, are sometimes fully aware that they are buying–and selling–forgeries. Wait, his biographer? Somebody is writing a true story about one of the greatest art forgers of all time? Yep, pay attention now, don’t look away….is it under shell number two?

At one of de Hory’s house parties in Ibiza, we are introduced to Clifford Irving, an American writer working on a biography of the art forger. In one unforgettable scene, largely because of the baby macaque chewing Irving’s ear, he tells us, “All the world loves to see the experts and the establishment made a fool of”.

Ironic then, that during production Irving himself is exposed as a forger, for fabricating a biography of the enigmatic tycoon Howard Hughes. Welles, laughing with us at the convolution he’s brought us into, tells us, barefaced, that this is just a film about a hoaxer, who is being written about by a hoaxer, who is being documented by a hoaxer. No sleight of hand here.

Welles in the editing room

For the last stretch of the movie, our dependable documentarian turns the camera around. Don’t worry, the fourth wall was obliterated in the movie’s first three minutes. We’re reminded that Welles got his break pushing one big radio lie (“War of the Worlds”). We’re brought along as he waxes on the fuzzy boundary between art and artifice (“What we professional liars hope to serve is truth. I’m afraid the pompous word for that is art”).

Through this film, Welles embodies a duality; that of both narrator and observer. It’s in this last stretch where Welles talks at us most though, and it is for this part that some call this work the first (and only?) “film-essay”. This is also where the film really swerves, where we might start to feel whiplash from all the ‘truthiness’. Without giving away too much, I think it’s fair to say that the best parts of this movie are true.

There is such pleasant irony that in documenting art forgery, Welles succeeded in making a truly original film. This movie was supposed to be a straightforward documentary by Reichenbach of de Hory. Then Orson intervened and unabashedly leveraged those unreal elements of cinema (voice-over, music, editing) to expand the possibilities of the non-fiction form.

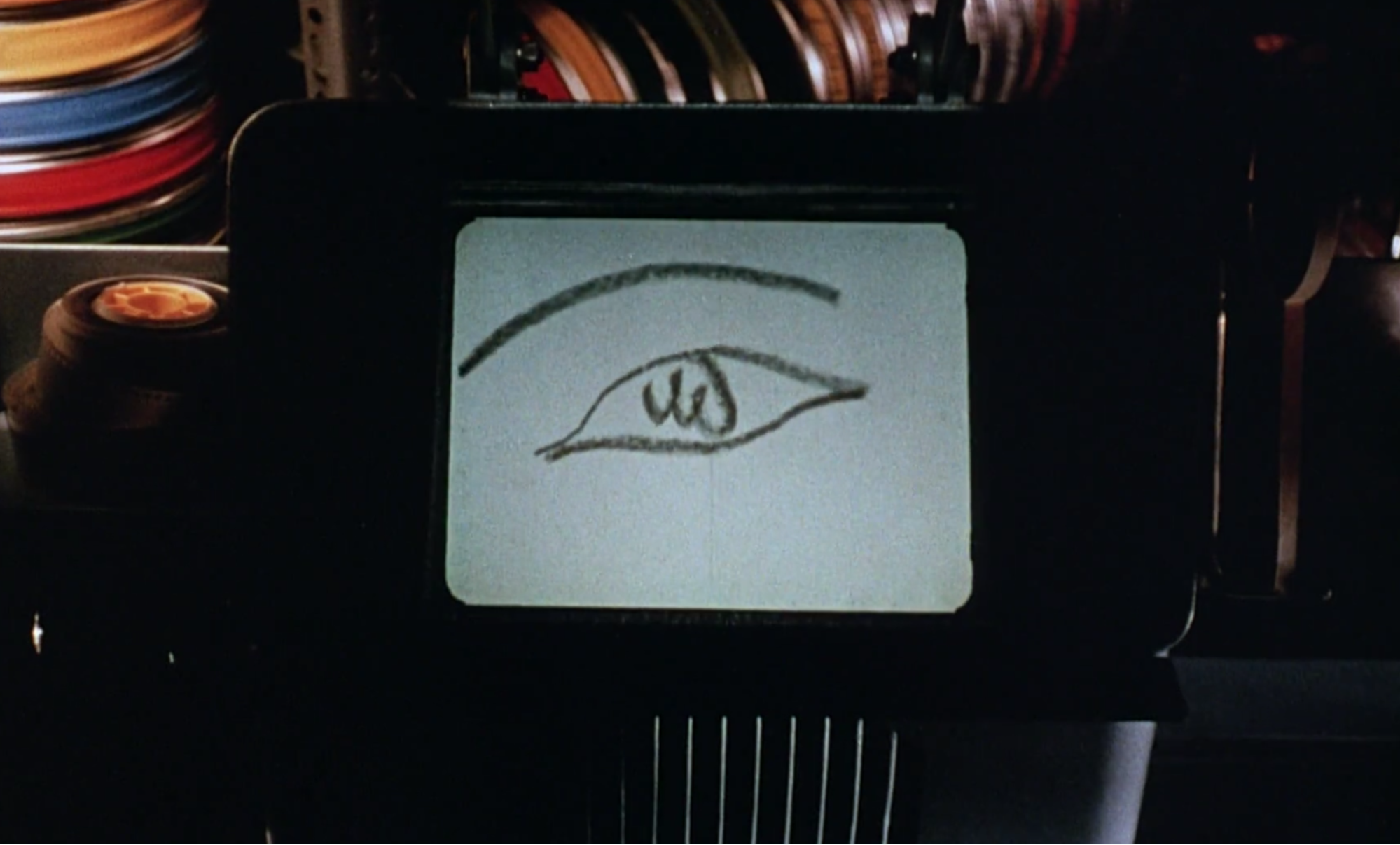

The eye of a fake Matisse

Oh, and about that editing? I love this movie for its cuts alone. In Welles’ hands, we careen around multiple pasts and presents, dodging in and out of the traffic of true events. I love the way Welles structures his cuts. Rather than a series of “then this, then that”, he strings sequences together along the logic of “but this, or that”.

In watching this movie you may feel like it’s being edited before your eyes. While some might find all this flash distracting, I feel that the exuberant editing lends itself to the overarching theme of trickery and magic. In its story and structure, F for Fake reminds us that in movies, and in reality, things may not be what they seem. Watch closely now.

Close-Up [Nema-ye Nazdik] (1990, Dir. Abbas Kiarostami)

At first glance, this film is more straightforward, maybe even honest. We follow the trial of an unemployed film buff in Tehran, Mr. Sabzian, who impersonates the celebrated Iranian filmmaker Mohsen Makhmalbaf, a peer of Kiarostami’s, to befriend a well-off family while pretending to write a film about them.

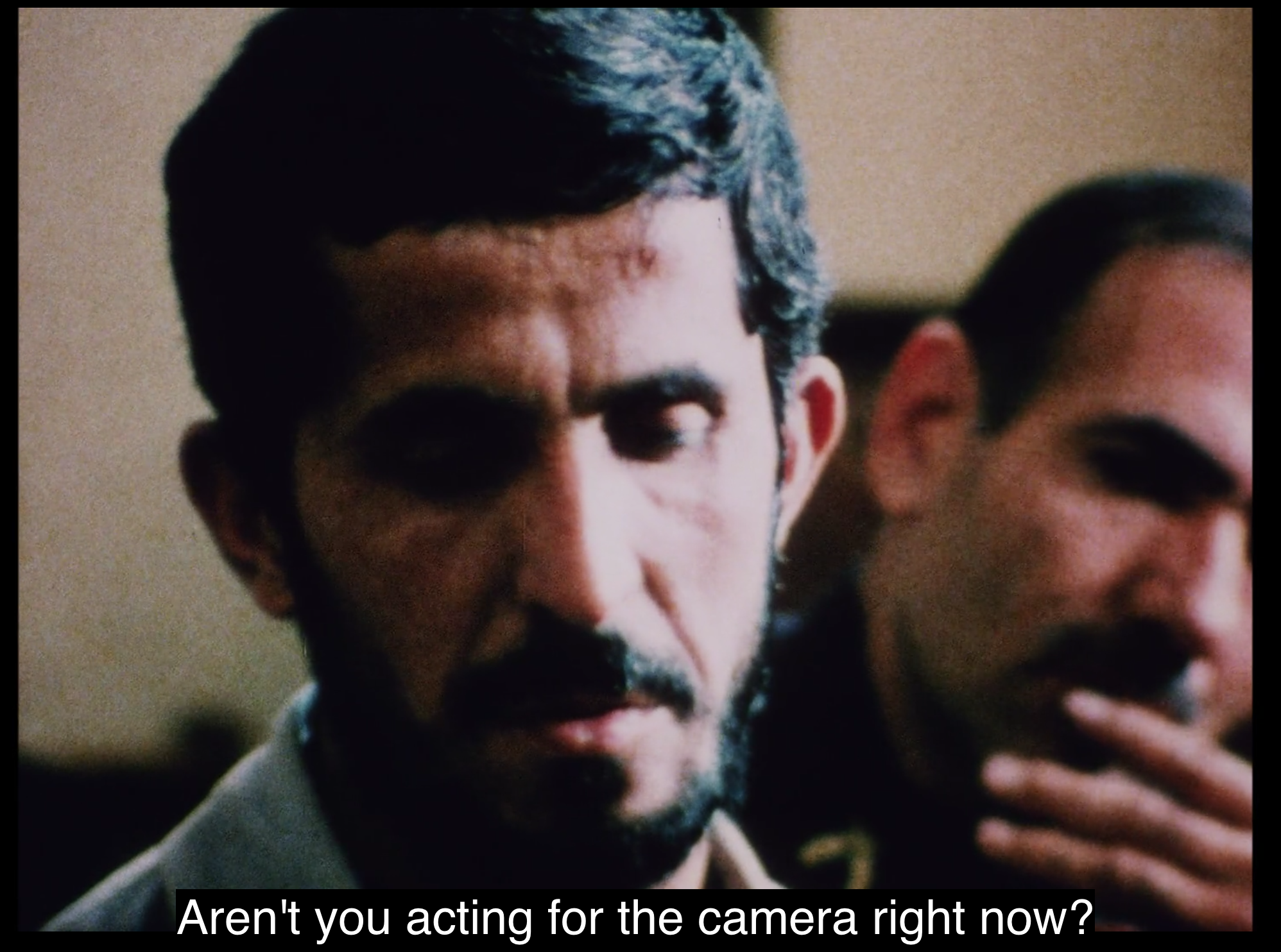

We watch, through prison wall glass, as Kiarostami asks Mr. Sabzian if they can film his trial. Here, when the director asks why Mr. Sabzian confessed to fraud, he responds “because that is what it looks like from the outside”. Kiarostami pushes, asking why he committed fraud? His response is Wellesian, “because I am interested in art and film”. In the courtroom, we hear our director outline the shoot to the accused: two cameras—one wide-angle, showing the whole courtroom, and one close up, fixed on the proceedings. We then watch, in mostly long takes, the trial of an imposter.

The reenacted arrest of Mr. Sabzian

This is a documentary, but one in which directors become lawyers, judges become actors, and actors become themselves (and vice versa). The unbelievable feat of this movie is that Kiarostami convinces those involved—the accused, the plaintiff’s family, the reporter who broke the story, even the taxi driver—to come together after the trial and reenact events. Put simply, this film features performances of people playing themselves. To me, these reenactments tear the veil between drama and documentary.

The movie opens in media res with one of these depictions of true events. We’re brought to what should be the peaking drama of Mr. Sabzian’s story, his arrest at the household of the deceived. Yet, here is where Kiarostami starts to play with reality, to decide for us what version of events are seen. His choice? We stay with the taxi driver, waiting outside as he pulls flowers from yard rakings, and playfully kicks a can down the street.

Kiarostami posing a question to the accused during the trial

Other action exists outside the frame, why can’t we see it? Here our director checks the urge to divulge through editing and flexes the incredible power of the camera to withhold. I also can’t stop thinking about the can. Its lazy roll down the street really happened, but is it what actually happened? This reenactment breaches the boundary between staged and unstaged. It forces us to ask if Kiarostami is authoring interpretation or documentation?

I’m inclined to believe Kiarostami is an honest broker of true events. The construction and structure of the film support this inclination. There are all the wonderful verité trappings. A boom mic dropping into frame. The clapperboard chopping. People stammering or scratching their temples. It feels like we are getting the raw data here. Kiarostami’s editing pushes this even further. Close-Up is notable for its lack of parallel action; there is almost no cross-cutting. The courtroom scenes are long takes. The reenactments give us singular perspectives.

Truth and fiction ride side by side in Close-Up

The end of the movie seems to relish in this cinematic truthfulness. In the movie’s most dramatic scene we are privy to the mishaps of filmmaking. The lavalier mic fails (“its old equipment”). A parked car disrupts the scene’s blocking (“no, don’t stand there”). And the shot is obscured by a crack in the windscreen. It all feels very real.

Or so I thought.

Kiarostami later admitted that there was no problem with the sound, “the fake [person] was too real and the real [person] was too fake”. So, he manufactured malfunction and invented the dialogue of the camera operators. Once again, he directs our attention to the difficulty of seeing any kind of complete picture. After all, there were only two cameras in the courtroom.

The Through Line

These are both art films about fakes. Both blend layers of the real, and are part documented present and part reenacted past. They’re obviously alike in their subject matter. Sabzian and de Hory are imposters of artists who share delusions of grandeur. In both, the directors lean into the looking glass, showing us, with the help of these hoaxers, how hard it is to depict true events.

These are also fake films about art. When I say fake films I mean that they deploy the elements of ‘movie magic’ to purposefully keep us on our toes. However, post-production is where the movies differ. Welles whirls around the editing room, splicing fragments from multiple timelines and realities. He is the great rearranger.

Kiarostami is more subdued, yet, I would argue the shrewder of the two in understanding films’ inherent duplicity. He recognizes, and wields, the fact there is always more going on than the camera will allow us to witness. It’s in Close-Up where we feel strongly that questions of representation are ethical questions. Whose perspective do we bear witness? Who decides? Through their craft and subject matter, these films exhibit the complicated responsibility that comes with depicting reality.

Are these movies better off with each other?

They’re certainly stand-alone, but together they make up stanzas in some strange song about so-called true events. We can see the imprint of these films in modern cinema. Chloé Zhao’s recent works (e.g., The Rider, Nomadland) are fuzzy fictions in which people play themselves. I think these films can also leave a personal impression. They make us think about what it is that we are “seeing” when we watch a movie: a lie? a trick? a copy? I would not say that these are ‘post-truth’ works, rather pieces of art that show us that life, like film, is made of fragments that each of us see and stitch together.

How to watch

Well caffeinated. First, F for Fake. Then, Close-Up.

Where to watch

I saw these both on Kanopy, the free streaming service associated with public libraries and universities.