***Spoiler Warning: Numerous Plot Details for Jordan Peele’s NOPE Included Below. Reader Beware!***

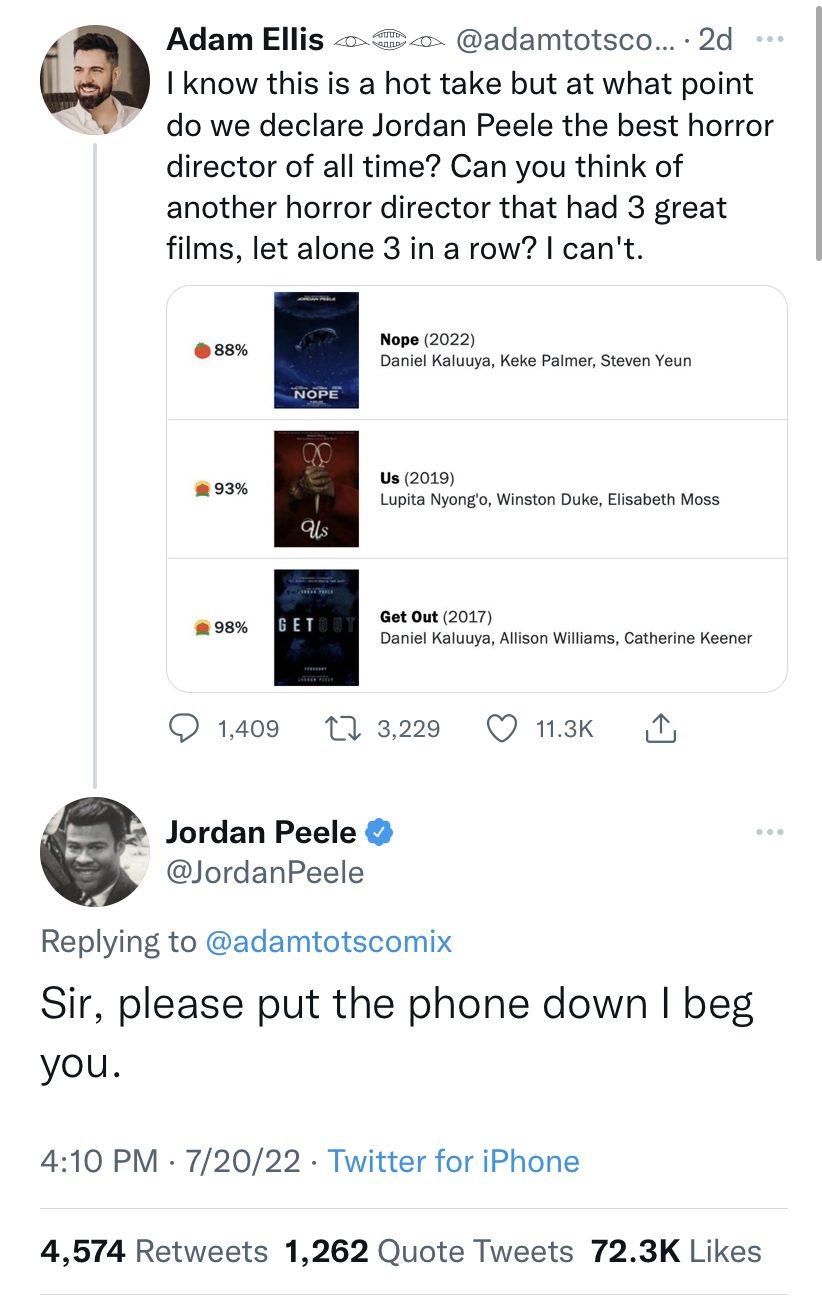

On the eve of the release of Jordan Peele’s third feature film Nope, twitter user @adamtotscomix cracked his knuckles and fired off a take so scorching, he earned himself a surprise reply from the director:

First and foremost, some A+ twittering. Three cheers for Peele, and for the wonderful app that made this moment possible and as of this moment still is not owned by Elon Musk.

Peele’s follow-up, though more gracious (boooooo! we want more drama!), was also the more telling of the two posts:

The Carpenter name drop is a timely one, as the septuagenarian slasher-master’s fingerprints are all over Peele’s third feature. Nope is a decidedly modern extraterrestrial western, built off the scaffolding of classic sci-fi horror; a gripping story about spectacle, exploitation, persistence, and obsession.

If that seems like a lot to fit into a two-hour-and-change genre movie, buckle up—because Nope is also a film about filmmaking, the intersection of art and commerce, the consumption and creation of media, fandom, trauma, gender dynamics within families, various iterations of grief, the struggle to maintain relevance in an ever-evolving industry, and how you’d handle hundreds of gallons of viscera being dumped onto your house in the middle of the night.

It’s also one of the best original summer blockbusters in years.

“How does he do it?!?!?” shriek the imaginary hordes of readers invented to segway gracefully into the next section of this review. And I’m glad you asked! Because as we’ve been warned throughout the runup to the film’s release, Nope is not what you think.

Come to the theater expecting a standard-fare popcorn invasion flick, and you might leave perplexed by the film’s patient, nostalgic pacing. Try to anticipate the ending, and you’re more likely to miss the point. In fact, it isn’t until the final credits roll, maybe even until you’re en route home reflecting, that the full picture starts to come together.

Nope begins biblically, with a verse from the book of Nahum: “I will pelt you with filth, I will treat you with contempt and make you a spectacle.” Suddenly, we pivot to a trashed sitcom soundstage, in the wake of some violent confrontation. A chimpanzee in bloodstained human clothing emerges, investigating the destruction around him.

Then, without explanation, another cut, this time to the ranch of our taciturn protagonist OJ Haywood (Daniel Kaluuya) and his father Otis (portrayed briefly by Carpenter alum Keith David). Here our story begins in earnest, with the mysterious death of Papa Haywood (struck down by a nickel from heaven, tough look for my guy) and OJ’s subsequent preoccupation with what he believes is a UFO hovering (and excreting inorganic material) above his home.

This is a familiar refrain in science fiction stories––tragedy begetting some kind of obsession with the unknown. Similarly predictable is the clash of personalities between OJ and his extroverted sister Emerald, who returns home to help out with the family business in the wake of her father’s death, despite long having felt shut out from the business and the masculine bond between her dad and brother.

As partial UFO sightings, animal disappearances, and inexplicable blackouts become more frequent, the siblings shift their focus away from their horse training and interpersonal drama, and onto the extraterrestrial, they are convinced now resides in a stationary cloud above their gulch.

Suddenly, there is a shift. That recognizable narrative of discovery contorts, and OJ and Emerald begin to scheme; not about learning more about the UFO, or defending themselves against it, but about capturing it on film as soon as possible in the highest cinematic quality. Their logic is jarring but acutely modern: inevitably, someone is going to make money off this thing, so why not them?

Little do they know someone else has beaten them to the punch. Local celebrity-ish, former child star, and current theme park proprietor Ricky “Jupe” Park (an equal-parts smarmy and wounded Steven Yeun) has already encountered the UFO (which he unironically dubbs “The Viewers,”) and is using the horses he has been buying from OJ as bait to lure it out as part of an attraction at his western-themed park, Jupiter’s Claim.

Things go predictably sideways for Jupe and his audience, but not before he reveals to OJ and Emerald that he was on set filming an episode of the fictional sitcom Gordy’s Home during the freak chimpanzee attack which opened the film. We’re treated to an extended, even more harrowing flashback to our cold open, where young Jupe watches from under a table while Gordy the chimp snaps after being startled by the sound of popping balloons and goes on a rampage against his human castmates.

In the moment, it reads as a bizarrely tangential piece of exposition. Less so when, after the UFO consumes and digests Jupe and his audience, OJ begins to speculate that this spacecraft is not, in fact, a spacecraft—it is a creature, one that does not react well to being put on display. “I guess some animals ain’t fit to be tamed.”

With this newfound understanding comes a new plan, one to lure the extraterrestrial creature into position to choreograph and capture the perfect shot. With the help of local electronics store technician Angel Torres (Brandon Parea) and eccentric cinematographer Antlers Holst (Michael Wincott), the siblings execute their daring escapade, chock full of unexpected twists and apparent sacrifice plays, and ultimately, in spite of the odds, make it out the other side with one exploded alien (popped like a balloon by a balloon, irony lives), and one expertly framed picture of the creature (by this point unaffectionately nicknamed Jean Jacket) for posterity. A happy ending!

Sort of. Because again, it’s not what you think. As the triumphant final shot fades, the dots begin to connect from Jean Jacket’s demise, to Gordy’s freakout and subsequent gunning down, to a comparatively innocuous early sequence of one of OJ’s horses bucking during a commercial shoot, all the way back to the opening biblical verse: “I will treat you with contempt and make you a spectacle.” These are not disparate incidents, not inexplicable attacks. The desire to make a spectacle out of a creature pushes that creature over the line, and when they react, they are punished for it.

It isn’t difficult to take the concept a step further: a cultural compulsion for documentation becomes a competition for the best documentation, which becomes a need to contort the subject of the documentation to make it perfect, which inevitably corrupts the subject. What are we if not constantly pushing each other over the line? What do we do to each other when we finally react?

It’s hard to overstate the degree of difficulty in presenting such heady philosophical musings to the audience while also making sure they have fun watching your movie. In a recent interview with Sean Fennessy of The Ringer, Peele articulated that front-of-mind concern succinctly: “I think people like movies more than messages.” In order to secret the film’s weighty themes inside an engaging, blockbustery package, the director relied heavily on his supremely talented cast and their ability to flip between charisma, introspection, humor, and terror on a dime.

That shouldn’t come as a surprise for those familiar with Daniel Kaluuya. Fresh off what should have been his second Oscar (rightly won for his portrayal of Fred Hampton in Judas and the Black Messiah, wrongly snubbed for Get Out), the British actor delivers a masterclass of stillness and nuance in his portrayal of OJ.

The horse trainer packs an indescribable amount of thought and emotion into the smallest of gestures, maintaining what might otherwise look like a disaffected expression were it not for Peele’s willingness to let the camera linger on him for long enough to observe the subtle changes. His hilariously matter-of-fact delivery of the titular “nope” after Jean Jacket drops a dummy horse through his car windshield transitions seamlessly into one of the film’s true moments of terror as he stares blankly into the glass-strewn dash.

It’s a leading performance much quieter than the more theatrical Fred Hampton portrayal, and more contained than the wide-ranging depiction of charisma-into-anguish-into-terror-into-fury of Get Out’s Chris–but one that’s no less deep or compelling. The closest things OJ has to outbursts (his enthusiastic daps with his sister on the porch, or his final determined turn to stare into JJ’s unfurling form) pack all the more punch for his restraint throughout the film.

Keke Palmer’s Emerald is a perfectly combustive foil to Kaluuya’s reserved OJ. From the moment she appears on screen, delivering an expressive elevator pitch for their family horse training business to a mostly-disinterested film crew (a pitch OJ had reservedly mumbled through moments before), Emerald dominates the frame.

Whether dancing around the house listening to Dionne Warwick in a Prince t-shirt, busting Angel’s balls, or celebrating her against-all-odds triumph over Jean Jacket (“nobody fucks with A1 bitch!”) Emerald is the charismatic heart of Nope beating against OJ’s grounded stoicism. And much like Kaluuya, Palmer injects layers upon layers of tangled emotionality beneath the electric exterior, ensuring that her outsized performance never slips into caricature.

What further elevates these performances is their consistency amid the unraveling circumstances around them. OJ remains quiet and determined even in the face of an unthinkable creature, with only little bursts of excitement breaking through. Keke is hilarious even when cowering in the corner of a blood-soaked house.

The supernatural does not supersede a person’s nature. There is an inherent realism to the way the core ensemble members maintain (or further reveal) their personality in the midst of catastrophe, one that is as telling (and far more compelling) than the most detailed exposition could ever be.

In a film preoccupied with the theme of staging the perfect shot, cinematography predictably plays an essential role. Here, Peele hands the reins to Hoyt van Hoytema, the DP de jour of IMAX-fiend and clock-obsessive Christopher Nolan. The results are among the best of the year.

It’s old hat to call the camera a character in and of itself, but the shifting perspective and choreography of Hoytema’s lens is uniquely essential in telling the story of Nope. The film’s sitcom-flashbacks opening is told through the eyes of Jupe, frozen and deliberately obscuring our vision of the carnage he’s hiding from. Its opening credits are revealed from what we will later realize is the perspective of Jean Jacket, rippling and Jaws-esque in its animalistic voyeurism.

As OJ runs from one of his first encounters with JJ, the handheld camera trails sloppily behind, often losing him from the frame while it anxiously tries to maintain a sightline on the UFO darting in and out overhead.

Peele and Hoytema are not reinventing the wheel here. From the aforementioned shark-vision of Spielberg’s Jaws to the heavy-breathing-backed Michael Myers sequences in Carpenter’s Halloween, horror directors have long relied on first-person perspective as a means to place us inside the body of an unseen killer. The difference here is the fluidity of vantage, the constant shifting from scene to scene and moment to moment in terms of who the camera speaks for. The seamlessness with which those perspectives shift speaks to the brilliance of both director and DP.

If Tenet fans are concerned that this approach might constrain Hoytema’s grandiose camerawork, never fear: the film’s expansive final set piece is its visual highlight (and its most characteristically van-Hoytema-ish), an argument for making sure to see the film on the biggest screen you can. Hoytema gorgeously renders a dusty California vista vibrantly dotted with multicolored Wacky-Waving-Inflatable-Arm-Flailing-Tube-Men, as a bright-orange-clad OJ races out to lure his extraterrestrial white whale into one perfectly captured shot.

The elaborate gambit pays off (narratively and visually), as just at the climax of the chase we are transported to the perspective of Holst as he documents Jean Jacket’s baited attack from an overlook. It’s a captivating visually captivating moment, but even more so it’s a brilliant filmmaking choice that justifies its spectacle by situating us within the sense of awe and achievement experienced by its ensemble.

The technical flourishes don’t end with the visuals, and neither do their careful narrative justifications. Though it should contend across multiple awards categories, Nope seems like an early shoe-in for Best Sound, as its sound design is integral to both the disquieting environment and the narrative of the film, often linked diegetically to Jean Jacket and its incursions.

The power-downs that precipitate the arrival of the creature slow the family’s turntable, inadvertently producing a haunting, chopped-and-screwed rendition of “Sunglasses at Night.” Environmental sound empties from the scene each time the creature arrives directly overhead.

Phantom shouts from former victims, likely mid-digestion, ring out like a demonic birdsong. Jupiter’s Claim park announcements return along with the electricity after JJ’s demise, just in time to tell the audience “it’s time to ride off into the sunset.” On the nose, sure; but impossible to not appreciate how well it’s pulled off.

In a recent interview with Shawn Fennessy of The Ringer, Peele explained “At this point, a bit of a reflection…or a mirror I should say. I sort of see my job and my responsibility, y’know, above all else, is just to take what I’m getting out of the world and turn it into story.” While in context he’s referring to the industry-adjacent setting of his latest film, that notion of reflection and interpolation feels inextricable from the signature referentiality of a Jordan Peele joint.

In Nope, the references are as numerous as they are evocative. The vomitous gore-shower instantly recalls everything from Carrie to War of the Worlds, while also providing us with our first hint that some things don’t sit well in the extraterrestrial’s stomach (a fact that will prove essential in the film’s climax).

Like the mask-obscured assault that opens Halloween, Gordy’s attack, while gruesome, is hidden from view by conveniently arranged furniture and the limited perspective from Jupe’s vantage. Wincott’s casting is, in and of itself, a nod to Alien: Resurrection and Curtains (and as an added bonus, is probably the closest anyone will get to having the literal voice of Satan in their movie).

Most overtly, the imagery of Jaws’ demise is revived in the Nope’s climax as Jean Jacket consumes and then is exploded from the inside out by the inflatable Jupe balloon. Here, as in Jaws, the triumph of victory is tinged by the awareness that none of this needed to happen if humans weren’t so hell-bent on turning a profit.

Of course, so much referentiality also reminds us of the bar set by Peele’s predecessors. Whether the comparison to decades-old classics is fair or not, there are a handful of key moments where Nope notably falls short. On first viewing, the languid pacing of the first act is meditative right up until it begins to drag.

Storylines for side characters like Angel, Antlers, and Jupes feel unnaturally abbreviated (perhaps left on the cutting room floor of the rumored 3:45hr first cut), and as such, some of their choices seem unjustifiable. The 11th-hour TMZ side plot is something of a narrative hat-on-a-hat, a rare moment where it seems Peele loses faith in our ability to comprehend the message.

Even so, Nope is ultimately a triumph by nearly every metric that matters, a film that demands rewatch as much as it excites on first viewing. Peele’s unique brand of recontextualized-classic-cinema-as-societal-commentary continues to thrive, and Nope makes it clear that a blockbuster-worthy budget only raises the ceiling of possibility for his work. That makes me even more excited for whatever he decides to make next–though I can’t imagine it will be what I think it is.