All interviews for this piece were conducted from September 2021 to February of 2022.

I produced a show in the Fall of 2021. I asked my friend Jackie Robinson, who is homeless and has lived in Chicago his entire life, to talk and a group of improvisers to make comedy off of it. Jackie described things like finding dead, breastless women as a child at Cabrini Green, and how he wanted to die. His hour-long narrative was immediately followed by a group of improvisers, including myself, performing a comedy piece inspired by his words.

There was something sanitizing about the experience, and something that turned the air on itself like when the wind turns and a firepit spits its smoke back in your face. It had the sense of remembering something painful and embarrassing that you’d tried to forget.

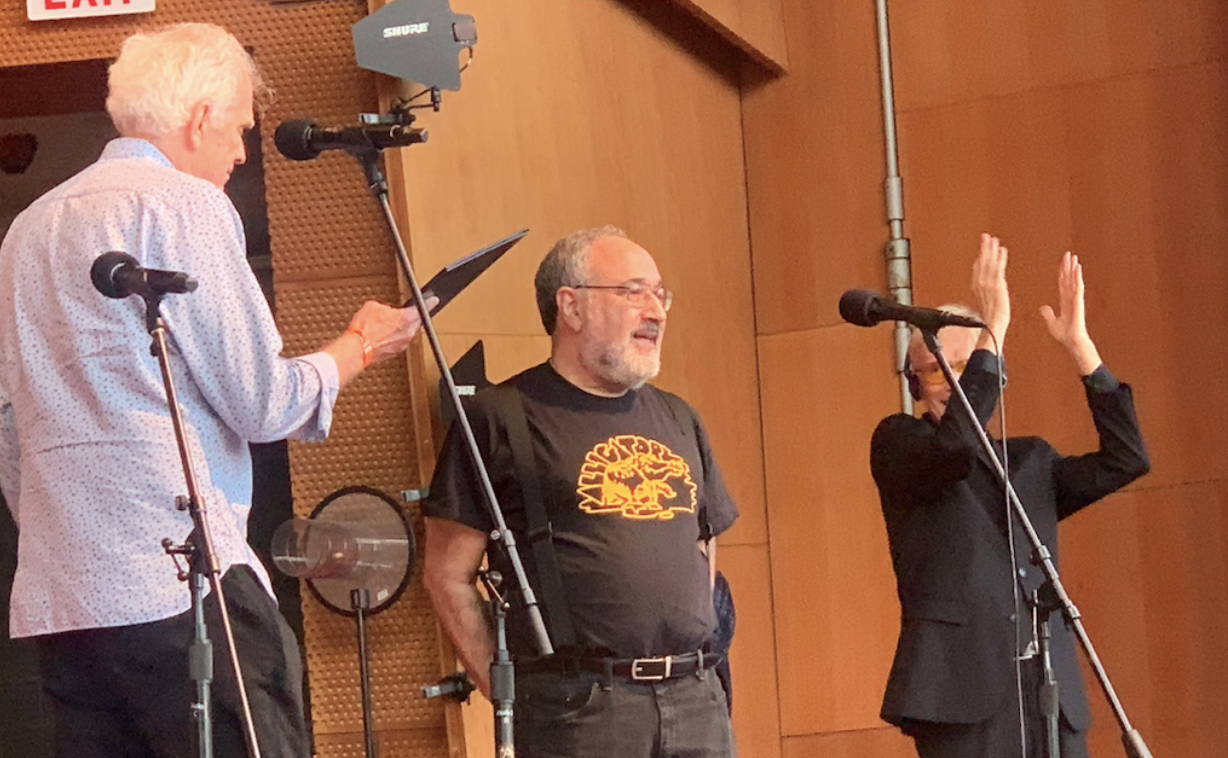

In 2011, Bruce Iglauer, the head of blues label Alligator Records, was interviewed in the Chicago Reader by David Whiteis. Iglauer defended not booking more Black artists, saying, “If I’m criticized…for not signing more African-American artists, the answer is: show me an African-American artist who has got a vision for where to carry some blues into the future, who is an efficient bandleader, who has their act together businesswise enough so that I can work with them, who doesn’t have a significant drug or alcohol issue, and who has live charisma, and I will take that artist real seriously.”

During its first 16 years, Alligator Records booked exclusively Black artists. The label only released their first album by a white band in 1987 with Little Charlie and the Nightcats. Something changed in the ‘80s and ‘90s in much of the blues as the notion of what was authentic shifted; what one artist ominously described as “the whitening.”

“It became less and less of a de-authenticator for white European musicians to be hired to back up Black singers. What started to happen as record sales diminished, as the music industry began to tank…you know, they do a French tour, they’ll bring over Toronzo Cannon and put a French band behind him, and go over to Greece and have a Greek band behind you. Same thing with Italy. I mean I’ve toured Italy with Italian bands…so the landscape changed.”

Many artists, like Ivy Ford, believe blues festivals should do a better job in their booking of Black artists. “I do think that festivals and events and things like that could have more Black artists headlining and more the face of the blues. Because right now, okay like for instance–when I go to someone and I say like, “oh yeah I play blues,” or like however it comes up, their first response usually is, I shit you not, “Allman Brothers, Joe Bonamassa,” who the fuck else, “Bonnie Rait, Beth Hart” and hey—I’m a huge Bonnie Rait fan—thick and thin, but that’s the first thing that comes to mind rather than Sonny Boy Williamson, Junior Welles, Muddy Waters. And it’s funny ‘cus I feel like it should be the other way around.

“And why there ain’t one damn Black-owned record label in the blues. And if there is–I mean maybe there is—but that’s like underground indie. The major ones are not. They’re all run, and have been, by white men.”

In my research, I was able to confirm that there are no major Black-owned blues labels. It’s a stunning fact, one that shocked even Toronzo Cannon. “Oh my god. That’s a shame. Wow, I’m sorry, brother. Hey, I wish I could call a lifeline on that one because that’s a slap in the chest.”

As Daphne Brooks noted in a piece for The New York Times from 2020, “The early record industry’s root-and-branch white supremacy and sexism have resulted in lasting structural inequalities in the label boardroom (where Sylvia Rhone of Epic Records is one of the few Black women executives), in the studio (where men outnumber women as engineers and producers) and in arts criticism (where white voices speak more often about Black music than African-American women do).”

From American copyright law that was used to cheat Black singers out of “their due returns” in the 1920s and ‘30s by deeming their music “composerless,” (Sound Effects, Simon Frith) to the modern day where Black musicians still rely on white-owned companies for distribution (Rhythm and Business, Norman Kelley), it could be argued that there has never been a time in American record musical history free from corruption.

But discussing racial inequity publicly in the blues world can be treacherous terrain. In 2020, Gaye Adegbolola was on a panel called Women in Blues at the International Blues Challenge, which is run by the Blues Foundation. She claims she was warned by three different people in leadership at the Blues Foundation not to be “political.”

Gaye Adegbolola: But, you know, how can you love our music and don’t love our history, or don’t embrace our history? You know, blues music is music about liberation. Blues music is about a way to get the pain out. It’s easier to sing about the pain than it is to go and shoot somebody.

Nico: Were any of [the people who spoke with you] Black?

Gaye: No.

Nico: Do you feel like the Blues Foundation has any issues with racism?

Gaye: Uh, yes.

Many people outside of the blues world might not be aware of the Kenny Wayne Shepherd incident.

On December 7th of 2021, Rick Leonard of the BLARE (Blues Lovers Against Racism Everywhere) community called in to a radio show featuring the leadership of the Blues Foundation. He asked how the Blues Foundation could nominate Kenny Wayne Shepherd for Best Blues Artist of the Year when he had a replica Dukes of Hazard muscle car with the confederate flag on it. It came out later that the confederate flag also adorned some of Kenny’s other, non-replica, possessions, including a guitar.

I obtained a transcript of the call, in which then-chairman Michael freeman and President Patty Wilson Aiden of the Blues Foundation respond to Rick’s comments.

Michael Freeman: “One of the things that we are not, is directly a political organization. We are a musical organization, and our awards are given for recognizing musical excellence.

“There are a lot of people who make a lot of music that have different views on this world or have different political alignments. I appreciate your position. I cannot judge somebody’s music based on a flag that they put on a car.”

Patty Wilson Aiden: “I do want to say something in that as a Black woman I’m particularly sensitive to the symbols of racism in this country. I’m also particularly focused on celebrating African American resources, whether it’s blues music, Fine Art, other forms of cultural expression.

“I am committed to coming up with and working with the Blues Foundation board and our constituents coming up with a meaningful outcome through a very engaged, robust, and authentic conversation.”

This conversation initiated a series of dramatic events. Mercy Morganfield, Muddy Waters’ daughter, wrote a passionate piece to the Blues Foundation asking, “What do you all think the blues is at its core? At its foundational roots? If not political?”

When celebrated white harmonist and lead singer of the Fabulous Thunderbirds, Kim Wilson, read Mercy’s piece and renounced all of his Blues foundation awards, the Blues foundation immediately sprung into action, rescinding Kenny Wayne Shepherd’s nomination and even kicking his father off of their Board.

When reached for comment, Scott Fitzke, current chairman of the Board at the Blues Foundation agreed there was racism in the blues. “Yes, there is. If look you at statistics and you look at the number of Black artists that are performing at festivals and booked in clubs, I think that there’s issues with parity.”

From his perspective, someone who embraces the Confederate flag, while a symbol of “racism and oppression,” isn’t necessarily racist.

Scott Fitzke: “I mean there’s little kids running around when I was growing up that had Dukes of Hazard lunch boxes, I wouldn’t presume that any of those people or all of those people were racist.”

Nico: “Were any of those people Black?”

Scott: “I don’t personally know anybody that’s ever had any Dukes of Hazard lunchboxes…”

Nico: “Have you ever talked to any Black people in your life about racism?”

Scott: “I’m not gonna go into that.”

Nico: “Do you feel like you’re pretty educated about the Black experience?”

Scott: “I think I am.”

Later, Scott explained that the Blues Foundation has been “very intentional about raising the topics of racism in the music industry.”

Of course, much of this comes down to power; who has the power to amplify their message and whose messages are ignored. While many of the cultural battles underway in the blues revolve around concepts of race, those on either side would do well to consider what incremental steps could be taken to improve the conditions for underprivileged performers. One area that might be a focal point is healthcare, considering many musicians’ lives revolve around it.

As Gaye Adegbolola told me, she kept her job as a teacher and didn’t become a full-time blues musician until she was in her mid-40s, in large part because she needed to keep healthcare for her son who is legally blind.

Rick Leonard believes the Blues Foundation should facilitate group plans like the one Gaye got for her group, Sapphyre. “With a group of 4k people the size of the Blues Foundation, they should be working with the labels to facilitate a group plan, cus you know, you and I can formulate a group plan and get eight of our buddies together and all of a sudden we got a group.”

It seems like the discussions around authenticity in the blues aren’t solely abstract. They point to questions like ‘what are we selling?’ ‘What can we sell?’ If the blues is truly a universal art form now, then there’s no problem with having any person perform it, no moral qualms. But if the blues is a space of corrupt racial practices, it calls into question entire identities, organizations, and histories. It begs the question, do we accept a corrupt system because it’s status quo?

A system like that would continue to fuck over those whose ancestors were robbed of their creation.

When I drive Jackie Robinson back from the show, he thanks me for bringing him out. He tells me he had so much fun and asks when we can do it again. I’m bringing him to a hotel called the Hotel Fullerton, where tenants with felony convictions and bankruptcies can get a room for 50 dollars a night. He gives the hotel owners his social security every month, a welcome change from sleeping on the streets, he says.

It would only be American, and you’d be excused of course, to wonder what he must have done to deserve it.