A couple of weeks ago this tweet from podcaster and former TMZ host Van Lathan came across my timeline. Lathan placed a meme with the cover of Jay-Z’s Reasonable Doubt and a picture of Juvenile’s 400 Degreez, writing “The album on the right is better than the album on the left.” To my surprise 400 Degreez was the album on the right.

You see, both these albums have had a profound impact on my life. Reasonable Doubt is my favorite Jay-Z album. I’m a huge fan of mafioso rap. The album is like an old friend that I visit often. But 400 Degreez…Well, that’s home cooking. It’s like going home to a big pot of gumbo at your mom’s house.

400 Degreez isn’t just an album. It’s a way of life. Like Juvenile, I am from New Orleans. Growing up, 400 Degreez was the fabric we came from in audio form. It honestly gave us purpose. You couldn’t ignore New Orleans any longer. The album is an institution in New Orleans like red beans and rice on a Monday. These are the recipes for culture.

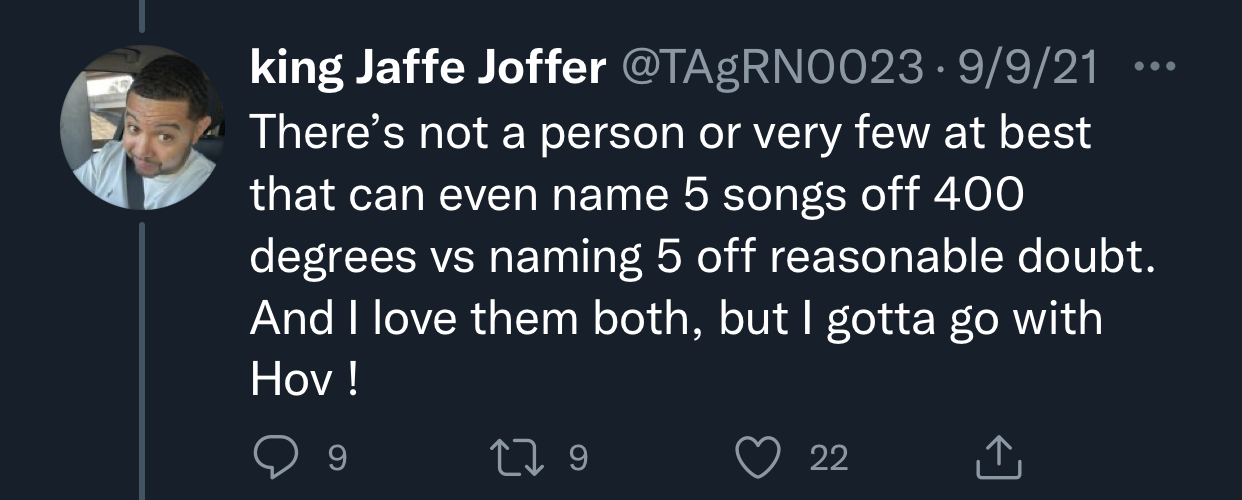

A deeper dive into Van’s tweet revealed the kind of response I had come to expect. His replies came from mostly non-southerners who quickly dismissed 400 Degreez as a classic album. Van’s followers considered it a regional success rather than acknowledging the juggernaut it was. But the album has sold over six million records. What we aren’t about to do is push 400 Degreez to the side.

Juvenile was born Terius Gray in March of 1975. He is the patron saint of the Magnolia Project, an uptown housing project in the Third Ward of New Orleans. Young Terius honed his early style with a call and response type rap, known in New Orleans as bounce music. Bounce is typically slick rhymes parallel parked over “Drag Rap” by The Showboys.

The “Drag Rap” instrumental became endearingly known as “Triggaman”; that loop became the foundation upon which Bounce was built upon. Juvenile had a bounce hit in the early ’90s titled “Bounce for The Juvenile.” Juvenile signed with Cash Money Records and, in a glorious national debut, 400 Degreez hit the airwaves in 1998.

Growing up in New Orleans the only thing separating me from Juvie was Louisiana Avenue. He was out and about in the city. Not a hard man to find. I watched Juvie from his humble beginnings to his peak (400 Degreez peaked at #2 on the Billboard charts in 1999.) Seeing someone from around the way “getting it out the mud”—making it to BET and MTV—was surreal. It made the term “anything is possible” feel, well, real!

For kids growing up in impoverished areas of New Orleans, we didn’t have many outlets. Juvenile gave us purpose, pride, and validated us as artists. From that point forward The Magnolia Projects were worldwide. We reached the top of the mountain. Rest in peace Magnolia (murdered by gentrification); Rest in Peace Soulja Slim.

Why is 400 Degreez so good? To find the answer look no further than your oven. While baking the optimum temperature is usually 400 Degrees. Yes, the oven can get hotter but you may have to get out of the kitchen if you can’t handle it. Juvenile created a preview of the South taking over. The album cover finds Juvenile upfront, towering over his beloved Magnolia Projects, summoning fire with his hands, surrounded by hot girls and diamonds, in their pixelated glory.

I mean, after all, he is a Cash Money record’s millionaire. 400 Degreez is the gold found at the end of the rainbow. It’s the silhouette of Bigfoot in the forest. It rests conveniently between heaven and hell, but still has access to both locations. It’s not good. It’s not bad. It’s the harsh realities of life combined with a manuscript of survival. It’s the audio form of “it is what it is.”

In 400 Degreez, Juvenile doesn’t just “rap,” he spits game to you in bar form. Many of his raps sound like they come from a man who has seen it all before. Chronicling life from project hallways to Zulu Ball (Zulu Ball is a large party for the coronation of the King and Queen of Zulu. It is thrown by The Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club. Invite only and please wear your Sunday’s best.) Juvenile is the wise old owl (or the three-eyed raven depending on if you are seated on the throne) detailing big baller parties and pitfalls in his section of New Orleans. He is like a hood reporter except Juvenile is way more gangsta than Don Lemon.

Firstly, we don’t have this project without Mannie Fresh. Mannie is the architect, orchestrator, and conductor of every album on Cash Money Records from 1993 to 2005. Fresh’s funky synths and hypnotizing 808s provide the backdrop for Juvie to run wild.

The album starts with “Ha”. A song that sounds like it was made from the distant future, possibly with the same tools that put the top blocks on the pyramids. “Ha” is so impressive because it’s an everyday New Orleans colloquialism. Juve is so creative he was able to take a hotline and turn it into a hot song. “That’s you with that badass Benz ha.” In New Orleans asking a question followed by, “ha” is rhetorical. The answer is already known. He’s projecting and emphasizing your accomplishments.

It’s like showing love to your friends and helping them stunt harder, “I know that’s your nice a** car. I see you bruh. Keep shining.” In the song, “Ha” Juvenile continually asks the hard-hitting questions that the Black community might call “the tea.” “Ha” is a simple song lyrically and it may seem easy to rap on. But Jay Z took a stab at it and failed miserably. I applaud his effort.

That’s you that can’t keep your old lady ’cause you keep f*****’ her friends, ha

You gotta go to court, ha

You got served a subpoena for child support, ha

That was that nerve, ha

You ain’t even much get a chance to say a word, ha

I know, I ain’t trippin’, don’t your brother got them birds? —Juvenile, “Ha”

These aren’t lyrics. These words are affirmations to live by. Every morning I look in the mirror point at myself and say, “You a paper chaser, you got your block on fire. Remaining a G until the moment you expire. You know what it is, you make nothin’ out of somethin’. You handle your biz and don’t be cryin’ and sufferin” followed by Amen. The last three bars of the first verse on “Ha” asks “You really don’t want to f***with them n***** ha You come up with them n*****ha

I want me a mill

To see just how it feel

No worries bout no bills, negotiatin’ deals

Buy me some sh**

Stuntin’ in this b****

Twenties be on hit

Everything legit —Juvenile, Follow Me Now

Ha was amazing but when the song was released the world didn’t feel it. They didn’t understand how to hear it. Or didn’t care to figure it out. The song that gave the album some traction is “Follow Me Now.” “Follow me” samples Tito Puente’s “Oye Cómo Va” (Mannie Fresh is a goddamn genius.) The beat is sped up a bit, but it feels like fun. It’s light and bouncy and Juvenile flows in and out of pockets with ease. The song took off. A star was born.

On “Ghetto Children” Juvenile proclaims, “in these times we gotta hustle. Cuz our pockets be hurting.” Later in the song, he advises us, “I got bills to pay I can’t be playing with you jokers.” Whether written in 1998 or 2021 the line still hits home. We are living in areas the government has forgotten. There isn’t time to look to the future. I have bills to pay. Life is too hectic to make a plan; I’ll figure that out later.

In these conditions, you feel stuck merely surviving. Sometimes you have to decide which bill to pay that month. I can guarantee nothing in my life is on autopay. Saving money was a luxury not afforded to the disenfranchised. I know not one older Black person familiar with stocks. Having money to play with is a foreign concept. The only thing that older Black people trust that they cannot see or touch is God.

Juvenile and Mannie Fresh were like Kobe and Shaq. Fresh set the table for Juvie to get easy buckets. Fresh broke down his defender off the dribble (via 808s and hi-hats) and Juvenile slammed it through the net. Juvenile was in full bloom exploring harmonies with catchy sing-songy flows. He was kicking knowledge with a bop. Mannie Fresh explained that he would normally come up with the chorus after making the beat, but with Juvenile that wasn’t necessary. Juvie came in the session with the look, the hook, and the experience. The bars were already written. Mannie Fresh structured the beats around the bars.

Later in the week, I went back to Van’s tweet. I was thinking about unwarranted hate on the album and replies like the ones pictured above. I was so mad I went looking for a fight. Reading further through the comments I saw a tweet that said, “400 degeez a southern rap classic. RD is a universal hip-hop classic. That’s the difference.” What the f***?”

But coming from the south I have seen this kind of disrespect all my life. I don’t know the guy who wrote those words, but if I had to guess this tweet belongs to a person from the East Coast. He believes that since rap started in the Bronx that it should remain in the Bronx. He probably accepts 2Pac, N.W.A., and the rest of the West Coast greats, but the South is outside the bounds of legitimacy. Of course, this isn’t everyone but if the “dead ass” Timberland fits. Lace it.

This Twitter user’s disrespect is not a one-off comment; it is systematic. You see it on radio, in literary works, and in other artistic forms we like to call culture. Because the product comes from the South, they are considered devoid of culture. We are certainly not worthy to be compared—and definitely not considered better than—anything coming from the East Coast.

But if you can get past this attitude and allow yourself to really listen to albums like 400 Degreez, you realize the deep connections Southern rap has to Black Americans’ roots. Southern rappers have the presence of black preachers Sunday in the pulpit. They can hurt, heal, anoint, or make you laugh.

The harmonies and chants are reminiscent of our ancestors working the field. Singing to numb and brutal reality. Singing for hope. They gave us pain, we found joy in song. They gave us scraps for food, we turned it into soul food. Those feelings never left us.

The South has had a ton of prolific artists. There’s no possible way you can hear Bun B, Lil Wayne, J. Cole, Rick Ross, OutKast (the disrespect shown to BigBoi has to stop), T.I., 8 Ball and MJG, Big K.R.I.T. , Killer Mike, etc. rap; and say, “you know for a guy below the Mason Dixon line, he. can put some bars together.” No, motherf*****. He can rap, period.

The East Coast has no special claim to universalism while the South is merely regional. These are the games White people played when they told us that the West was the true (and only) standard-bearer of culture. We know that s*** is a lie. Why replicate this pattern of cultural elitism for the sake of degrading Southern rap?

Bias towards southern rappers isn’t a new concept. Our Black counterparts on the East and West Coasts have long looked down on us. But we are still doing what you do. In fact, any trash given to us we turn into a pot of gold. We are filled with magic.

Outkast, one of the premier poets of our time, felt that disrespect at the ‘95 Source Awards. They won “Best New Rap Group” that year. After hearing their names called the audience reacted with a smattering of approval but also a whole lot of ridicule. The awards took place in New York. OutKast went on stage. Big Boi grabs the award, looks at Andrè, and says, “So what’s up Dre.” Andrè, normally reserved and quiet, was pacing back and forth. You can tell he is pissed. Andre 3k stepped to the mic and says, “the south got something to say.” From that moment nothing was ever the same. That one event started the “Harlem Renaissance” of southern music. The South has been running the world of rap ever since.

“400 Degreez” is the embodiment of day-to-day life for Black Americans. Not just in New Orleans but across the world. The album is tangible; you can feel the vividness of struggle. Growing up in an area where death is always around and tomorrow is uncertain, you have to keep your head on a swivel and still live life to the fullest. The album feels like a celebration of Black life in the South. Black people are living in cities with high poverty, high crime, and a lack of resources. Still, we rise. When I die please play 400 Degreez front to back at my funeral. No need to hire a preacher. Juvenile did enough of that on the album. If I ain’t a hot boy, then what do you call that?

The first line in the title song sets you up for the greatness to come, “you see me, I eat, sleep, shit, and talk rap.” All four are vital components of a lyrical genius. Can’t argue with facts

This is just phenomenal and poignant. Brilliant work my dude

“Still We Rise” like a flame burning at 400 Degrees🔥

this is just plain excellent – very well done. 400 degreez forever.