In 2018, Fox News bloviator Laura Ingram told Lakers superstar LeBron James to “shut up and dribble.” Her comments came during an on-air segment meant to chide James and Kevin Durant after they expressed outrage at Donald Trumps’ open embrace of white supremacy, but the quote took on a symbolic life of its own.

In a single dismissive sentence, Ingram revealed that cultural admiration for Black athletes had a price tag attached to it, requiring them never to make white audiences uncomfortable or challenge structures of power. After the clip of Ingram made the rounds on social media, Shut Up and Dribble was adopted as a title for a Showtime docuseries examining the history of social activism in the NBA.

Now, in 2022, battles over player activism have intensified, but also adopted a formula of sorts. It goes something like this: An NBA player speaks out on a social justice issue. The comments don’t need to be revolutionary. Even the vaguest whiff of social activism initiates a full-scale backlash that filters through Fox News and the major social media platforms. The sports press throws chum into the water by constantly playing clips while asking the player if they “regret their comments.” Failure to back down produces another wave of political rage from the right. The left is outraged by the outrage online. Individual stories fizzle quickly, but the cycle continues.

For all this struggle over activism among athletes, an underlying assumption embraced by almost anyone involved is that, if not for players’ advocacy, the NBA could be free from national politics. For many fans, watching their team battle it out on the court feels like an escape from the hardship of daily life, including the echo chamber of America’s deeply partisan politics. Yet, the truth is that even outside today’s era of player activism, basketball, like all professional sporting leagues, is a deeply political enterprise.

No sport exists in a cultural vacuum. The social structures that determine our markets and shape our political and cultural identities are playing out in the NBA.

Beyond a Boundary

The overlap between sports and politics can be difficult to discern. However, a surprising source may be the most revealing on this topic: the Trinidadian Marxist, C. L. R. James (1901-1989). In 1963 he published Beyond a Boundary, a book ostensibly about cricket, but also about so much more.

I first read Beyond a Boundary about a decade ago. A British friend of mine who loved cricket told me it was the best book ever written on the sport. I knew nothing about cricket at the time and I still don’t. But I knew C. L. R. James. He was a towering figure of Black revolutionary thought, a leading intellectual among British Marxists, and the author of Black Jacobins, one of the earliest and most powerful portraits of the Haitian Revolution. Nothing about this background suggested to me James would also write about cricket. Implicitly, I viewed sports as a subject unworthy of serious intellectual engagement. James proved me wrong.

Americans are notoriously turned off by cricket, viewing its Victorian modesty as an odd sight. But James’s book is not just teatime and wickets. Rather, for James, cricket is a method of analysis, a means of understanding class, race, Trinidadian national culture, and the political relationship between colony and metropole. Beyond a Boundary is widely considered one of the greatest sporting books of all time—the book that gave birth to the field of sociology of sport.

One thing that makes Beyond a Boundary so compelling is that it is part autobiography. Growing up, James was a good cricket player—a lover of the game—but his talent lay mostly as a budding intellectual, writer, and lecturer. The Trinidadian cricket league of James’ young adulthood was firmly grounded in colonial logic; the most desirable (but not always the best) teams were dominated by lighter-skinned players from the country’s upper classes. James, who did not come from much wealth and was relatively dark-skinned, was invited to play for one of the wealthy, light-skinned teams because of his intellectual reputation.

“So it was that I became one of those dark men whose surest sign of…having arrived is the fact that he keeps company with people lighter in complexion than himself,” James recalled about his choice of cricket team. “By cutting myself off from the popular [working-class] side, [I] delayed my political development for years.”

The game of cricket arrived in Trinidad as part of British colonial rule throughout the Caribbean. James, however, rejects treating it as solely an imposition of Western culture. It was that, of course, but it was also more complicated. By the time James was coming of age in the early part of the twentieth-century cricket had become a part of Trinidad’s national culture. It was what he had always known and a game he grew up loving.

Throughout the book, James talks fondly about the beauty of the game but is equally drawn to the way social systems poured themselves onto the cricket field. The game reinforced colonialism by creating a stratified system for teams, but rivalries between dark and light, rich and poor, played out on the cricket pitch, mirroring internal battles over British rule.

When Black players began entering professional cricket leagues in Britain in the 1930s, Trinidadians celebrated their successes as a vindication of their island. The success of these players from the Caribbean in England was a step toward political independence back at home. Beating White British players at their own game proved the colonial mythology of racial inferiority was a lie.

NBA as Method

But what does cricket or C. L. R. James have to do with professional basketball in 2022? The answer has less to do with James’s particular analysis—the NBA has its own colonial logic, but a very different history—than a recognition that professional sports can be a methodology for understanding our social and political moment. Like any sports league, the NBA is built on narrative and structures that reveal much more than what happens on the court.

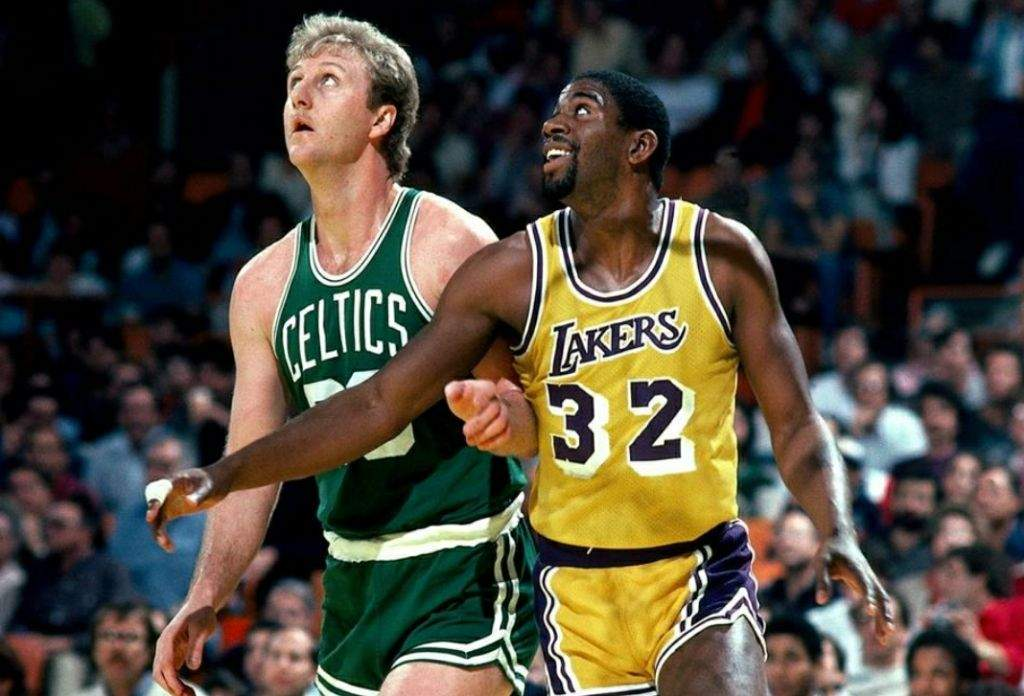

There are plenty of historical examples to turn to. The 1980s era of Bird versus Magic was not just two amazing players duking it out; it was the “great white hope,” as the press dubbed Bird during his 1979 rookie season, against the “streetball” flash of Magic Johnson.

It was also an early era of superstar-driven brands and mass commercialization, which has become a defining feature of all successful professional sports, along with many college ones. Major corporations wanted NBA stars to sell hamburgers, shoes, and sports drinks. Names like Michael Jordan, Shaquille O’Neal, and Kobe Bryant had international appeal at a time when owners of capital were expanding into global markets. Similar to the movie industry, star power (or franchise players) became a logic onto its own. The economic value of an NBA team is not just measured in winning championships, but the fame of its superstars and their branding power.

To talk of “branding” somewhat misses the point. In truth, we tell stories about players. When LeBron James famously declared he was “taking [his] talents to South Beach” in 2010, he instantly became a villain who betrayed Cleveland for money and status. Forbes magazine declared him “America’s most disliked athlete.” Still, as Sam Anderson remarks in a recent New York Times magazine profile of Kevin Durant, James’s decision represented a new era of player autonomy, at least among franchise players.

Decisions over team-building began to shift from executives’ conference calls to superstar player group chats. Whatever you feel about the optics of James’s spectacle, it is no coincidence an erosion of executive power and the vilification of James went hand in hand.

Like all parts of American life, race and capitalism are deeply enmeshed in the operation of the NBA. To talk of the NBA as a method is not just recognizing this, but actively working to unearth it. By all means, shut off your critical brain and enjoy watching your team. Just remember: what happens on the court is only part of the story. The myths the league tells about itself, and what those throughlines reveal about political and economic structures, is where the big picture appears.