We all go to the movies for the same reason: to escape. COVID-era theatrical attendance has plunged to about half what it was pre-COVID because there’s “escaping” and then there’s “dying,” which admittedly is a form of escape, but not one you want to experience for the price of a ticket and popcorn.

In its purest form, watching a movie in theaters is about submitting to what’s on-screen. We identify with the characters as well as the sensations captured through the camera. When we take our seats at the local art house we’re giving ourselves the freedom to become somebody else.

Mitski Miyawaki gets it. In fact, that transformative, freeing moment shapes the thesis of her new record, Laurel Hell, out last Friday:

Let’s step carefully into the dark

Once we’re in I’ll remember my way around

Who will I be tonight

Who will I become tonight

She hums on the opening lines of “Valentine, Texas,” Laurel Hell’s first track. Taken on their own, the sentiment is unremarkable insofar as the movies are concerned; Mitski’s lyrics just as well evoke the image of two lovers going to bed together for the first time, or the first time in a long time, or maybe even the umpteenth time in their relationship.

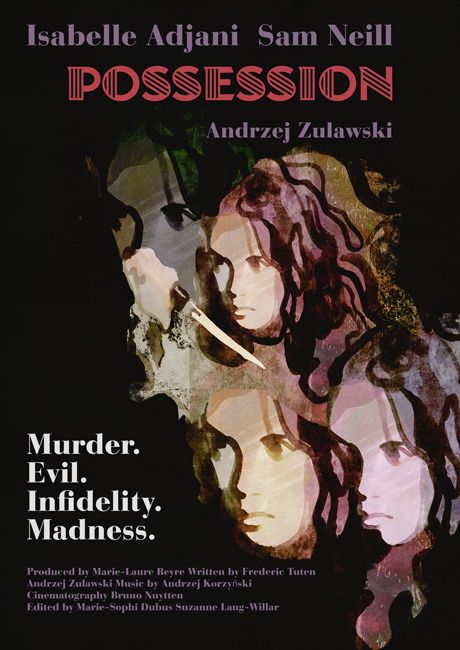

But Mitski is well-known for her love of the movies, horror especially, and the video for Laurel Hell’s lead single, “Working for the Knife,” recreates the most famous sequence from Andrzej Żuławski’s Possession, which celebrated its 40th-anniversary last year with a sparkling 4K restoration procured by France’s TF1 Studio. With these details in mind, divorcing Mitski’s words of this implicit meaning feels like a dereliction of duty.

Then “Valentine, Texas” ends, “Working for the Knife” begins, and the connective tissue linking Mitski to the movies and the movies to Laurel Hell strengthens. “I cry at the start of every movie,” Mitski sings over a punching bass drum and chainsaw synth. “I guess ‘cause I wish I was making things too.”

In the video, she casually kicks off her high heels and then, with a flip of her head, sends her cowboy hat flying. As the sequence continues, she strips away her duster coat, fully displaying her azure two-piece ensemble, and flails from surface to surface inside The Egg—a tame but effectively evocative imitation of Isabelle Adjani’s tour de force freakout performance in Possession’s subway scene.

Possession is the kind of film where you’re more likely to cry at the end than the beginning, but Mitski has such a clear love for Adjani and Żuławski’s accomplishment that it’s easy to imagine her crying through the whole thing.

Laurel Hell speaks to more than Mitski’s fondness for horror and for movies, naturally: Infidelity, loneliness, isolation, and forgiveness, among other themes. But there’s a bond cemented between the singer, her subjects, and her style that fuels the album all the way to its closer, “That’s Our Lamp,” where Mitski finds herself in the same place she starts out: “I’m standing in the dark / Looking up into our room / Where you’ll be waiting for me,” she sings, supremely melancholy, on the song’s final verse.

Laurel Hell manages to feel “cinematic,” such as music can feel cinematic. Yes, Mitski likes movies. Everybody “likes” movies. But Mitski’s interest in cinema as a medium that’s separate from, but nonetheless relates to, music provides Laurel Hell with a unique foundation where each track feels like a short film unto itself.

That commencing question—“who will I be tonight?”—bakes into the record as a whole, but with a slightly narrower scope. Forget about “tonight”: Who will Mitski be from one song to the next? On “Stay Soft,” she’s “your sex god”; on “The Only Heartbreaker,” she’s “the loser in this game” and “the bad guy in the play”; on “Love Me More,” she considers whether or not she could be a “new girl,” but she’d have to lock herself up in her home to avoid screwing up the same way she has for apparently 15 years.

Eventually, Laurel Hell arrives at its penultimate track, “I Guess,” a dirge for a friend whose companionship had such influence on Mitski’s identity that she can’t fathom who she’ll be without them; “I’ll have to learn / To be somebody else,” she cries over keys’ thick, haunting reverb.

Anyone who knows loss knows what she means. The deaths of our loved ones change us. But Laurel Hell is rooted in such a specific kind of change, the change we experience when we go to the movies, that when Mitski sings about becoming somebody else, the sentiment takes on an auxiliary meaning.

Mitski becomes “somebody else” on each track, after all, hopping from genre to genre, aesthetic to aesthetic, like she’s constructing an homage to the whole gamut of era-defining 1980s music: New wave, synthpop, dance-pop, Avant funk, post-punk. It’s worth noting, too, that the 1980s practically burst at the seams with movie musicals like Earth Girls Are Easy, Purple Rain, Pennies From Heaven, Little Shop of Horrors, Labyrinth, and Dirty Dancing. Laurel Hell functions as an interdisciplinary roundabout for the pop culture of that vaunted, over-romanticized decade to flow through.

Typically, present-day art made to ape the sights and sounds of a particular period miss what makes them memorable to begin with. Mitski apes nothing. She simply writes her songs and matches them to a feeling, then matches the feeling to an attitude captured by the necessary mode. “Should’ve Been Me,” a chirpy song about being two-timed, sounds a bit like a lost A-ha B-side, a mismatch on paper that makes sense in practice given the song’s emphasis on compassion.

“The Only Heartbreaker” strikes a similarly up-tempo chord but provides Mitski with her own personal confessional; “If you would just make one mistake / What a relief that would be / But I think for as long as we’re together / I’ll be the only heartbreaker”.

Picturing Mitski belting out these tracks beneath the spotlight’s harsh glare from center stage takes minimal effort. Laurel Hell’s theatricality is part of the point.

It’s certainly part of the pleasure of listening to the album. Laurel Hell is as rich in tone as it is in craftsmanship, and image-heavy despite the straightforward, stripped-down, quality of the lyrics. Mitski disguises nothing. In disguising nothing, though, she Trojan Horses everything into Laurel Hell. This is her personal movie theater. We’re invited to see and hear the world the way she does, and all the better for it.