What I’ll say first is this: It is unquestionably Ray Allen in He Got Game.

It’s not even very close as to what the ‘best’ is, though picking a ‘best’ turns out to be the uninteresting part. As with most things in life, there is a lot less value to the proposition ‘what is the best?’ than there is to: ‘why is this thing the best?’ And so we’ll look at that.

This is ultimately a silly exercise, but we’re Music Movies & Hoops after all, so addressing this subject almost feels like fait accompli. So here are some baselines:

- NBA and WNBA players only. I’m sure there are plenty of great actors who played in college, but I don’t have infinite time. Honestly, the number of professional women basketball players-turned-actors is very slim as well.

- No self cameos. There are thousands of spotlight roles for NBA players to juice up a film’s box office appeal. Especially if that movie centers around basketball. I wanted to focus on the word ‘performance’ so players as themselves in non-starring roles are out. Jordan’s & LeBron’s turns in their respective Space Jam(s) qualify because they are both lead roles.

- Films only. Again, I don’t have time to go searching for every TV show on which Rick Fox did a three-episode arc.

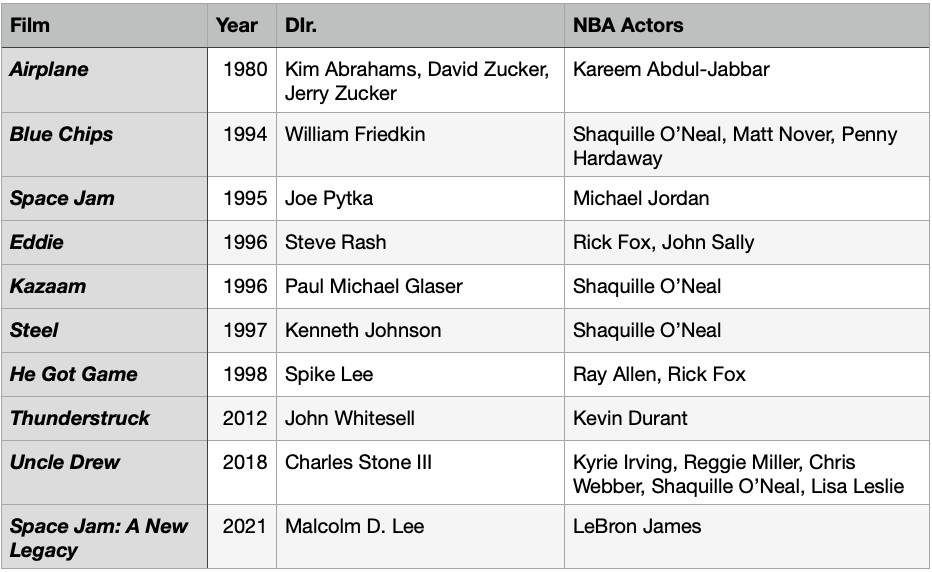

Ok, here are the films that were considered as part of this exercise:

The mildly shocking thing is: that’s kind of it. There are just not a ton of films that star NBA players. Some, like Eddie and Space Jam, have cameo upon cameo performance. These are obviously meant to spark the joy of fandom, imbue the film with realism, or pump box office sales. But as far as NBA players taking up the task of acting? There are not a lot more than what I’ve listed.

Again, we’re struck with a far more interesting question: Why is that? Here’s my theory:

Being a professional athlete of almost any kind takes a psychopathic level of commitment and luck that excludes the practice of many normal-person things.

The NBA in particular has a giant pool of talent to pull from, because basketball is, well, popular. Everyone likes it. Everyone plays basketball outside when they’re kids. Some even play a little school ball. Some are good enough to play in high school. JV, Varsity. Some are good, but get pulled away by 10,000 other interests: football, art, acting, girls, economics. Maybe, maybe, maybe, some will play for a good college. Maybe D2. Good enough to tell their co-workers years later that, yeah, they played a little college ball, and maybe they still have a weekend pickup game at the Y. Knee-brace required.

Maybe they even played D1. Got a damn-good education too, and now run a successful marketing company. Ever thought about going pro? Yeah, they thought about it but really, it’s just a handful of guys that are gonna make it, and most likely they would’ve ended up grinding it out in Latvia.

Maybe they were great though. Maybe they were great, and they put in the work to become greater. Maybe also, they won the genetic lottery and sprouted to an even seven feet in their junior year of high school. The sweat and the blood and the hours paid off, and by the time they’re a freshman in college, the NBA is an inevitability (as long as they stay healthy that is).

And then they make it, and not only do they make it, but they put in the hours and hard work to rise above all the other people who made it this far. All the other guys who spent early mornings and late nights at the gym. All the other guys who shot free throw after free throw after free throw in their spare time. They rise above. They become a superstar.

And then someone comes along and asks them to be in a movie.

You see where the problem lies? That level of commitment necessitates eschewing the very concept of ‘well-roundedness’. It requires singular dedication. Not that NBA-level athletes don’t ever develop into normal people, but to reach the absolute, super-star peak of professional sports, everything comes second to basketball.

So then to be invited to operate on that same level, but in a field so wholly different than anything they have ever done, is a monumental task. Acting requires different forms of movement, different repetitions. It calls for different tunings of social mimicry and relationships. (It is not easy.)

Kareem is the forerunner of all this. But Kareem, to me, is not naturally comfortable in the acting chair. He’s stilted and his comic delivery is choppy. He did make the case, though, that big-time NBA stars could move out of the arena and onto the screen. In addition to writing a really enjoyable column for The Hollywood Reporter, he’s had a very prolific career as a frequent cameo.

Successful crossover does happen, though. Rick Fox is the main example. During and after his NBA career, he proved himself to not only be capable, but at times a very good actor, especially with his stint on Oz. John Sally too, has had a bevy of good roles. But it’s rare. Why the hell should an NBA star care about acting? Why should a studio executive want to cast an NBA star in a movie, when they have spent their entire lives devoted to something else? (hint: money).

One maybe not so nice reason why I think that Rick Fox has had a more successful-than-most acting career is that he is closer to average height than his contemporaries. Being seven feet tall is not conducive to giving a relatable performance. That’s not to sound exclusionary, and it’s not to be mean, but most people are not seven feet tall, and there is an inherent surprise factor in seeing someone who is. It is obviously not insurmountable, but it is a barrier to entry. Fox, at 6’7”, probably has an easier time fitting in at a party.

This is also not to say that putting your very successful and very tall NBA superstar in a movie, or better yet, building a movie around your NBA superstar of choice doesn’t ever work out. Space Jam was a huge hit, despite me not going to see it when I was little. Jordan is pleasantly good in it, albeit playing a version of himself. But Space Jam—both Jams—actually, are much more an exercise in production animation than they are about ensuring their star gives a mega-compelling performance.

I pity Jordan and James (not really, but go with it) for having to spend what must have been months looking at tennis balls and green screen muppets with middle-aged guys asking them to lift their hands one inch higher on the next take. I dare say it’s hard to draw a competent performance out of some of the most gifted actors alive when they’re thrust into the machinery of demanding visual effects.

And now we should talk about Shaq. Shaq has made three movies: Blue Chips, in which he plays a recruit of wild boar basketball coach Nick Nolte, Kazaam, in which he plays a genie come to life to grant Francis Capra three wishes, and Steel, where he suits up as an injured soldier in a robot-cop-esq mecha-suit to dispense with baddies.

I have not included Grown Ups 2, where he plays a cop named Officer Fluzoo. I am going to argue that this is a cameo, mostly because Shaq is being utilized in this film almost exclusively for his Shaq-ness and not for his acting ability, but also because I did not want to watch it.

Shaq is a charming, natural, and engaging actor. It’s the most surprising revelation of this project. He’s not flawless, and it’s obviously always SHAQ, but he’s charismatic! He’s got a huge smile, and he knows when to deploy it for maximum effect. In Blue Chips, he’s quiet and funny and all the things one could want from a seasoned pro, but if you think Blue Chips is a movie starring Shaq, I’ve got a Nick Nolte to sell you.

It’s a shame that his other two films are such horrific duds. I loved Kazaam when I was little, but on rewatch as a thirty-two-year-old, it’s, um…not good. Steel is better, but it’s still just a total mess. Confusing in tone, lame in action, and sort of a mystery as to who it was made for, Steel was a humongous box office disaster that effectively ended Shaq’s leading man career. It made $1.7m. Yep, total.

We don’t need to talk about Kevin Durant in Thunderstruck.

So let’s come back to Ray Allen and why he’s not just good, but great in He Got Game. He is great, by the way. He’s unstudied but easy. He’s nervous, but his nervous energy brings a truism to the role of Jesus Shuttlesworth, a kid on the eve of the biggest decision of his life. The answer to the given ‘why’ is as ordinary and as old as the hills: making movies is a collaborative art form.

He Got Game is one of the defining films of the 1990s, directed by the most important and skilled director in the last 30 years. That helps. It’s scored by Aaron Copeland in an iconic, depressing embodiment of disillusionment Americana. That probably helps. It stars Denzel Washington, the greatest actor alive, in one of his most complicated and vicious roles. That helps.

The movie is great, and this is not to take away from what Allen is doing in it, but to suggest that having a network of support consisting of some of the greatest minds in American filmmaking can lift an individual performance to another level.

Allen is raw, but his rawness is reinforced by the rawness of the scenery, the locked camera. His rawness is juxtaposed by staccato violins crying out for the once-great countryside. He doesn’t need to be giving an exacting and precise performance because Denzel Washington is doing that opposite him. The two of them work off each other. One brings his reactionary and deft thespian training, the other, his experience growing up playing basketball and trying to make it to the big time. Allen doesn’t need to wrench his performance to be about the criminalization of Black fatherhood, because the film itself is telling us that story.

Jesus Shuttlesworth is sweet and nervous while trying to be hard. What better casting than to choose someone new to the role of acting itself? Allen had played one season in the NBA by the time principal photography began for He Got Game. What genius to have a man who’s at the beginning of something, to contrast with the exacting and final nature of the American criminal justice system.

Allen lifts the movie and the movie lifts Allen. That is always the way of the best films and best performances.

I am interested to see what comes next. Is there a superstar NBA player who can work in the big-budget non-stop world of superhero blockbusters? Is there another Rick Fox out there with the interest and talent for a second act? I don’t know. However, after all this searching and analysis, I can say this: They should make an Uncle Drew 2 because the movie kinda works.