It’s surprisingly easy to imagine a world in which Oliver Stone’s Any Given Sunday (1999) was directed by David Lean (Lawrence of Arabia). It’s vast; a chugging, muscular film unappreciated in its time and overlooked still, having been released to critical indifference the same week as Stuart Little 2 and The Talented Mr. Ripley. The sweep of it is all-encompassing, yet centers on two figures who are simultaneously mythic archetypes and undeniably human.

Any Given Sunday has an understanding of place, scope, and people that looms large in the vast expanse of its vision and is positively in the cinematic tradition of David Lean, of Sergio Leone, even of John Ford. This film’s desert is the turf. Its war is the game. It is an epic in the truest sense of the word. And it’s the greatest sports film of all time.

Oliver Stone made Any Given Sunday at a time when acclaimed 80’s directors were becoming cinematic dinosaurs, artistically struggling to survive in a late-90’s dominated by the meteoric rise of indies anchored by darlings like Quentin Tarantino and Gus Van Sant.

Brian De Palma had just made Snake Eyes, the first flop of many in a long, slow slide. Joe Dante was doing fuckin’ kids movies. Stone himself was coming off the (in hindsight, underappreciated) critically and commercially disappointing U Turn, and the character at the center of Any Given Sunday—the tortured, aging football coach Tony D’Amato, played to barely coiled perfection by Al Pacino—is that guy.

D’Amato’s stooping. He’s always looking a little lost, a little tired, and his verbal explosions communicate a man struggling to understand himself, the shadow of his team’s former owner looming over him as he tries to imbibe new models and imperatives set by that owner’s daughter, Christina Pagniacci (played by Cameron Diaz in what should be seen as a top-five role, if we’re being honest). When Pagniacci looks at D’amato and says, “The players are just not responding to you,” it’s hard not to see Oliver Stone contained within. D’Amato’s paternalistic relationship with the third-string quarterback thrust into the limelight almost feels like an explanation from Stone to young directors: “See? You need me to help you through this.”

It’s not just these three actors that give the film its gravitas. It’s full of character actors and people who know their roles—performers who lean into what they’re required to do and are willing to live on the edges of scenes, ready to take the spotlight for a moment and disappear again. They were keenly selected for their presence, and each of them takes what they’re given and makes the most of it.

These characters have hopes and dreams, duplicity and honesty, kindness and cruelty—they act according to the shifting landscape of the film, sometimes big, often small, and make themselves feel bigger than the space they’re given. It lends Any Given Sunday an authentic, human anchor that carries us through its messy hyperscope.

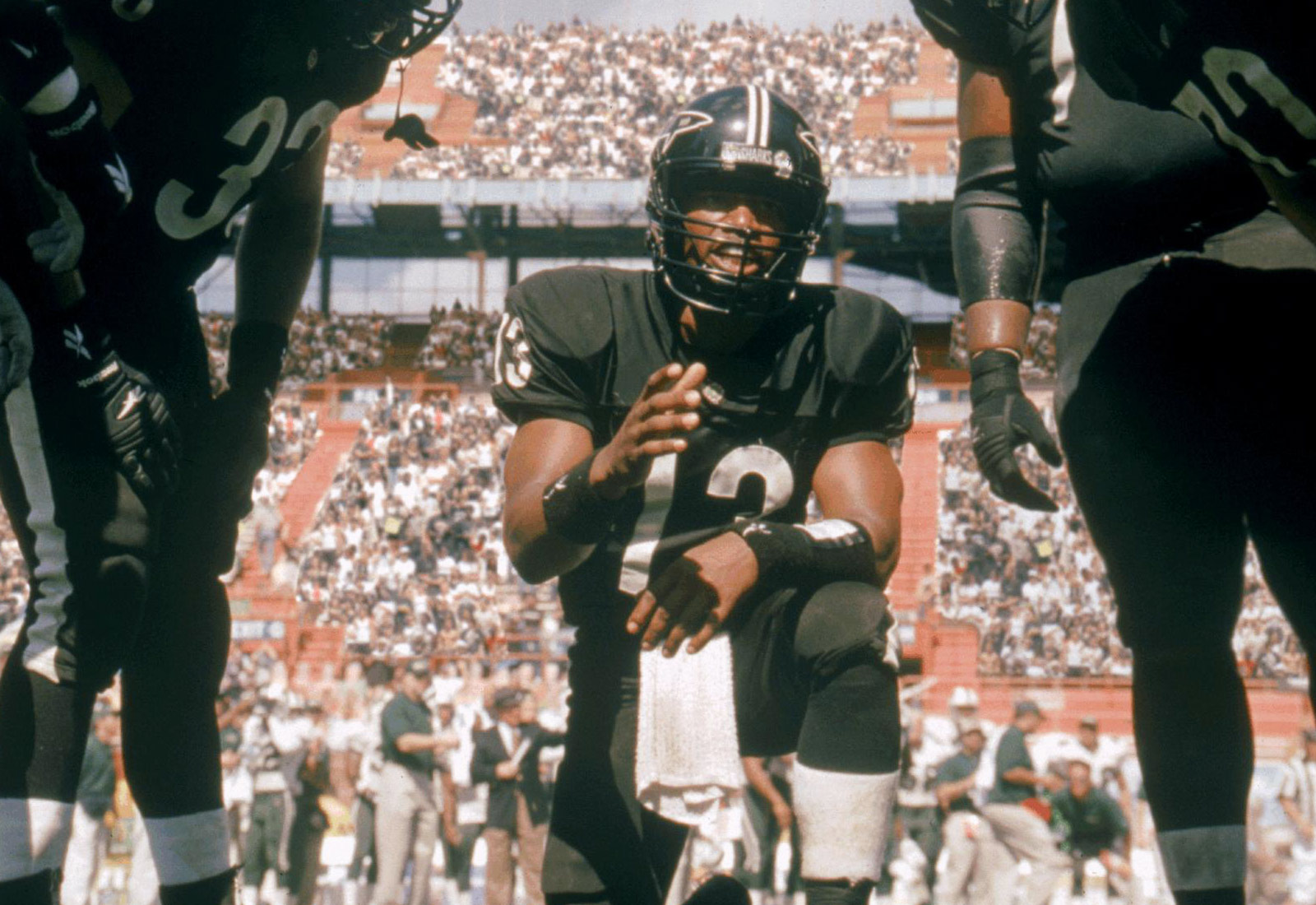

“Messy” may be too unkind a word. Any Given Sunday sprawls. Its geography is endless, unbound by the conventions that govern lesser sports cinema. On the field, it has its big moments, sure, but it understands that the story of the game is in the details. The little handoffs, the tackles, the collision of bodies after a hike. Too often do sports movies simply provide a quick overview of the game, head to the locker room, and then come back so we only witness the final, decisive moment in detail. Not this one.

Stone’s directorial style has always been one of asides, mixed formats, absurd cuts, and jarring editing. Removing himself from the introspective, obsessive scope of films such as Nixon and JFK, this style sings. Stone’s confidence rides a peak that allows a single scene to juggle the dozens of narratives that run simultaneously in sport: the personal, the economics, the charity work, the locker room squabbles, and the analyst narratives. He knows how to slow down, how to speed up, how to live in the sharp intake of breath before a touchdown, and to look away at something else during a particularly boring quarter.

To put it simply: Stone understands why fans watch the game. Not just for the big moments, but for the little stories that form the spine of those moments, that make them feel earned and worth it. That contextualizes them, not just in the context of the locker room, or perfunctory, small communities, but in the context of the entire entertainment world.

No one just watches sports for the inspirational, clean-cut sanitized Coach Carter bullshit. No, they watch sports for the showboating, the sex, the off-kilter rants, and the occasional scandal.

Is Any Given Sunday hyper-realistic to the point of being unrealistic?

Maybe, but that’s just how realistic die-hard fans make sports in their own mind palaces. It’s a purely selfish, individualistic world that Pacino’s D’Amato has found himself aging into. There’s a gold-plated ooze of big money and corporate power that shines in the yellow-tinted cinematography onto every character’s skin and the sky itself, like capitalism itself has been soaked into the emulsion. When Cameron Diaz looks at Al Pacino’s Super Bowl—sorry, Pantheon Cup—ring, the look she gives is covetous; a desire to penetrate a hedonistic, man’s world that she’s cinematically on the periphery of, one that Stone rips into with a frenzy.

Any Given Sunday occupies almost no space in the constant discourse and listicles which rate, rank, and extoll the hundreds of sports films that have come out over the years—films that follow a natural, God-given structure of conflict and character, that should be easy to make, but aren’t. That structure lends itself to a certain kind of danger, slipping often into the saccharine, the turgidly inspirational, and the clichéd. It comes with the territory, and Any Given Sunday isn’t innocent here, but it earns its brief lapses into trope.

There is a kaleidoscope of so many plots and characters—some picked up and dropped at a moment’s notice, others that stick around for a bit—that you’re just a little unsure how you got there, but you understand the exhaustion as you’re hurtling to the finish line.

When Al Pacino makes his final speech, a four and a half minute banger filled with cliché and earnest delivery that rises to a crescendo where it really is impossible to not feel, you may question what it all really means, and what unfinished threads were left along the way, but isn’t that what sports is?

What fan remembers every single narrative of every single game and everything in between that emerges and disappears over the course of a single season? All you know is you watched your team come out the other side, better and stronger and more equipped (or disappointingly, less equipped) to take on what’s next. You’ve seen guys who will go that inch with each other, and in that moment, when Al Pacino tells everyone to heal, as a team, you’re ready to go that inch with them.

You haven’t simply lived the highlights, you’ve been in the shit, assaulted by the camera, the editing, the emotional explosions, and the barrage of extraneous—yet essential—material.

And that’s what makes Any Given Sunday so compelling. It still lives in the natural order of the sports movie but infuses it with the chaos that’s sorely missed in favor of family-friendly entertainment. There’s the inspirational speech, the coach with demons, the ambitious player not ready for his moment, all of that. It comes with the territory because it has to. No screenwriter would be brave enough to break that trend, because that would be unrealistic. It’s anathema to the function of sports narrative; these clichés are essential to the game of football, to any game really, in story or in real life.

Screenwriter John Logan understands this necessity, but his antidote to the formula was forcing it into a grown up version—the kind with childlike playfulness, teenage lechery, and the existential dread only adults fully contemplating their mortality and age in the world can feel.

It understands the racial and paternalistic and sexual contradictions and totalizing inadequacies of the sports world; the cruelty of a patriarchal industry dominated by white men at the top and everyone else at the bottom.

And yet, it still has optimism and humor and joy in spades, right up the cotton candy ending. It’s remarkable that a film like this is able to bear its own weight, from the 243 page script to the 3000 individual cuts in the edit.

There was nothing quite like it before. There’s been nothing like it since. It’s likely there will nothing like it again. It feels like the age of films like Any Given Sunday is over. A two-and-a-half-hour sports film in the age of Marvel would feel anachronistic, especially through Stone’s chaotic lens. Even Stone himself understands this. Snowden, his last theatrical feature, was an oddly muted affair relative to the brilliantly executed frenzy he’s known for.

It’s true, imagining a version of Any Given Sunday directed by David Lean is easy. Collectively, sports fans may not consider the games they watch or the teams they follow as an epic. But these are lengthy, ongoing stories of dynasties, kings, ripped Grecian gods, power brokers, and court jesters.

However, it’s just as easy to imagine a version of the film directed by Dan Fogelman (This Is Us). When games and narratives are viewed tightly, week-to-week, they don’t feel like epics. They feel like perfunctory narrative movements in an endless soap opera. That’s what watching and following sports is. That’s the tension that fans observe in their obsessive dedication to the game. That’s what creates the traditional sports narrative; this whiplash between the micro and the macro. And that’s Any Given Sunday.