All interviews for this piece were conducted from September to December of 2021

At Obama-era Oberlin, it seemed like most people were doing their best to move beyond race. So I tried my best to believe them. We studied the white masters, living and dead, in music history, and music theory, and my weekly workshop with the other composers of my class. This was, after all, a universalized music tradition passed down through well-worn European tracks.

Over the course of my study, I became painfully aware of the unspoken. Many of my favorite composers had lived in societies churning with wealth scalped from Black and Brown bodies. And what’s worse, they hadn’t mentioned it.

I’m mixed; my mom’s white and my dad’s Black. I grew up all over the place, moving eight times before middle school, and depending on where I lived, my identity was coded differently. In upstate New York, I’m Black enough to have the n-word shouted at me from trucks and to be glared at from across the bar by a group playing a country song on the jukebox with a lyric about lynching.

In Pennsylvania, I’m Black enough to be told, “you’re not really Black.” It’s hard to say what Blackness is for these people, maybe a blaccent, maybe a shade.

My mom, a race scholar, actually taught me about The Nod. We were walking around Oakland, California when I was probably 8 or 9 years old. She noticed some Black folks making eye contact with me when we passed, and I would just smile at them. When she told me I was supposed to nod, I asked why, and I remember her being flustered, probably not wanting to saddle too much weight on me. “It’s just because of this shared thing, because of your Blackness.” After I learned about it, I would do it every chance I could, reveling in this unspoken secret I was a part of without quite understanding why.

Ironically, the first time I was treated rough by the cops was in Venice, Italy. I was there with my parents, who were conducting an anthropological field study. I was 14, striding down cobble corridors with a cockiness I emulated from my uncles. The two Carabinieri officers, military police who carry machine guns, pushed me against a wall before I even saw them and demanded my “documenti.” I pretended not to speak any Italian and acted indignant, yelling that I was American until they let me go. They had likely thought I was a Moroccan immigrant.

These experiences aren’t that unique. And so, I wanted to probe deeper into questions of race and authenticity in the blues to better understand some of the fault lines in the community.

I ask blues singer Gaye Adegbalola if the lived Black experience is an important part of the blues, and she says there’s something to be said for it. “Same, like if you haven’t been to a Black church, then you really don’t know what the Black church experience is. And most all of your Black blues musicians have come through the church. Have you been to a Black church?”

I explain that I have, with my grandma in Oakland, but that it wasn’t the kind of church I think she’s talking about, and she laughs. “Oh, I don’t know. I don’t know. My church wasn’t a ‘rocking’ church. and most of your Southern Black churches, a lot of the hymns are sung as dirges. But you know, there’s an experience that says you put on a church hat and you strut, you know?”

For Toronzo Cannon, the blues is intimately linked to his forebears. “My ancestors were slaves, and what they went through here in America, it’s like my grandfather was born in 1924, my grandmother was born in 1926, imagine what they went through? My grandfather was born in Jackson, Miss. and he was a fair-skinned man. He light-skinned, Blacks might be looking at him like, “Okay, here’s this light-skinned dude.” And he married a dark-skinned woman from Memphis, Tenn. They came here in 1944 to Chicago, looking for a better way to live.”

He explains that true blues people, “know that there’s no politically correct blues.”

“Think about the ancestors. And it may not be your ancestors, but they are ancestors. And you can’t act like this just blues dropped out of the sky and didn’t have anything to do with nothing oppressive. I know blues has turned out to be like a fun thing that can make you happy, but there’s certain blues where you have to understand that it came from pain. It came from people being killed. The blues didn’t just land here because everybody was cool back in the 1800s…

The blues is supposed to be the truth. I know some people just want to see blues entertainers talk about a woman that’s mean blah blah blah, that kind of thing, but it’s like that’s not what’s all blues is about—a woman leaving you or a bad relationship. The fact that you can’t buy a house in a certain neighborhood could be the blues, you get passed up by a cab, you get substandard medical because you don’t have insurance.”

Nora Jean Wallace has noticed that in some places “people just want you to shut up and play, and they don’t want to be uncomfortable with your song.”

For her, the blues inheritance began right away. “My grandmother, she used to run a juke joint. And that’s where my father and his brother and cousin used to play at. On weekends all my uncles, his wife, my cousin, and stuff we used to get together on the weekend…We used to always peep through a hole in the door in on the grown folks. And they playing music and dancing and stuff, and that’s what I was brought up in, the music.”

She was born in Greenwood, Mississippi, but, “when I got ‘round ‘bout 11, my parents, they moved out on a plantation called Equal Plantation, and that’s where I growed up at.” I’m shocked to hear that her dad was a sharecropper. Those days feel so far away, but hearing it from the perspective of Nora Jean, it doesn’t sound half bad.

“Well, it’s just so much freedom. And you don’t have to worry about shooting and all this stuff that’s happening now. And we used to play ball. And after church, we used to go on the airplane field and play baseball, and it was lots of fun.” She laughs at the memories. “My father used to raise a big garden, a lotta organic food, you know?”

She tells me about her dad’s band, The Sasha Boys. “He was a vocalist and a drummer. My uncle, he played guitar, his name was Henry Wallace. And my other uncle, he used to play the washboard. And his cousin, my father’s cousin, Buddy Smith, he used to play bass. And my father’s friend, his friend was Isaiah, he used to pull the broom. They used to call him Broomstick, ‘cus he used to play beautiful sounds with pulling the broom.”

Nico: “Where did they perform?”

Nora Jean: “Right around in the country. They never made it big, you know. They never made it big, ‘cus they was too busy on driving tractors and all that other stuff.”

Rick Leonard, who created the Facebook group Blues Lovers Against Racism Everywhere (BLARE), grew up in North Carolina during Jim Crow where the KKK “would march on Saturday afternoon” and “it was nothing to see a cop picking up his klan uniform along with his cop or his sheriff uniform at the dry cleaners.”

He explains, “in the mission statement for BLARE I respect the rights for everybody to play the blues, and whiteness always comes back with ‘oh well you’re saying that white people can’t play the blues, and Black people can’t do ballet.’ No no no no, if you respect the culture, if you respect the legacy, if you respect the heritage, you will be first of all booking according to actual blues. No matter the band, it’ll be factual. A perfect example: Eric Culberson, Charlie Musselwhite, and Lightnin’ Malcolm all grew up steeped in Black culture, they are rare but they are practitioners of authenticity.”

Nico: “The blues is not necessarily multicultural but it can be multi-racial?”

Rick: “Yes. Yes.”

There are blues musicians who disagree with this premise, like Larry Taylor, son of Eddie “Playboy” Taylor. I ask him if there’s such a thing as an authentic blues musician who could be white and he’s adamant there can’t be. “Because if he’s playin’ the blues, where did he get it from? Who did he get it from? How did he get it? He got it from someone that’s Black.”

But what about a white person who grew up in a Black community? For Larry, the fact that, “if he grew up in the South, he hung around Black people to learn what he learned” would negate any claims to authenticity.

Nico: What if we had someone who was Black but didn’t grow up in the blues, and started playing in their 20s?

Larry: “That doesn’t make them an authentic blues musician, man. In order to be an authentic blues musician, you have to live this, man.”

For Larry Taylor, in order to be an authentic blues musician, you must first be Black and then “live” the blues, which means in part learning from Black blues elders.

Critics of positions such as Larry’s might argue that it steers close to racial essentialism. Bio-essentialism of any type argues that there are innate qualities predetermined by the body you have. But I’m curious about aspects of the Black experience that might be impossible to communicate to someone who is not Black.

I ask blues scholar Dr. Adam Gussow about this theoretical “embodied divide,” and he explains that when he did his dissertation in 2002, there was very little work being done on the connection between the blues and the “extreme racial violence” that was “all over the blues autobiographies.”

“I talk about this journey a little bit in Whose Blues, but I think that it was BB King’s statement and the way that he represented his own youthful confrontation in Lexington, Miss. with the hanging body of somebody who had been killed, it was kind of a legal lynching actually. I think that sort of set me on a journey to try and understand these resonances.”

Dr. Gussow: “I think you’re intrigued by what you would call the white-Black divide and you’re sensing an epistemological divide that should somehow necessarily cramp transracial understanding. Am I right?”

He is, but I explain that I’m coming from the perspective of phenomenology.

Nico: “So you would not say our physical bodies predetermine our lived experiences.”

Dr. Gussow: “I’m not a pre-determination kind of person. I mean the physical body that you possess, or I possess, is read entirely differently, let’s say, if we fly to Brazil. So if we’re talking race, I mean there’s so much that’s contingent, there’s so much revelation possible for people when they take their embodied selves with all of the associations that they have, all of the experience that they think they have, and they moved simply to a different venue or a different country. They find, or discover, that they’re being taken entirely different ways that lead to new experiences, and maybe an alteration of the idea that they were carrying that helped shape who they were.”

This suggests that the American Black experience is localized, but it’s worth mentioning that white supremacy has, in some senses, been exported globally. Though its manifestations and degrees may differ, its impact may not seem avoidable for those with Black and Brown bodies.

But what one person wants to avoid can be another person’s golden ticket.

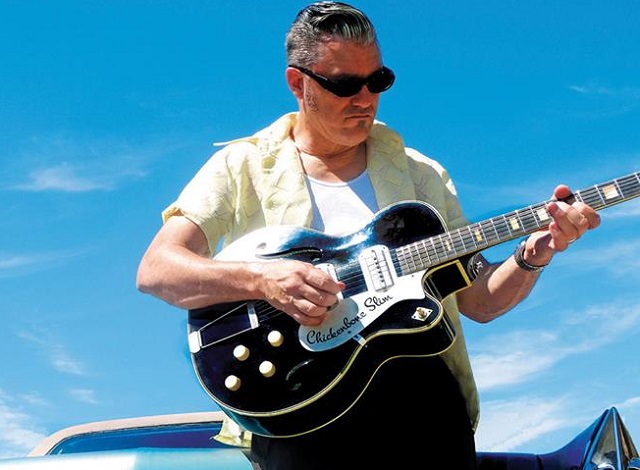

I’m talking with one veteran blues player when they mention a band called Chickenbone Slim and the Biscuits, which is led by a white bandleader. She says, “I had well-known Black women blues singers who are elders come out and tell me this madness had to stop.” She sounds audibly upset.

“This kind of gaslighting, I mean who can’t understand how hurtful a name like Chickenbone Slim and the Biscuits are? I mean it joins so many racist tropes that it makes the head spin, yet and still people will deny that it has any—even Black people who think that that is a nice guy, know him personally like, ‘Chickenbone Slim, shit, he’s been around forever, man’ yeah, well you know what else has been around forever? Change.”

Chickenbone Slim, or Larry Teves, is a Bay Area-based musician originally from Santa Cruz. I ask him what he gets the blues about and he says, “Everyday life. Just every- there’s not a person- you know- I don’t know how old you are- life is hard for everyone, and everybody has problems. But there’s a commonality to that that we all relate to, so do I get the blues? Oh heck yeah. Women, work, life, right? Everything gives you the blues one way or another, it’s kind of how you deal with it.“

When I ask about his name, Chickenbone tells me he used to be called Scary Larry and the Bogeymen. He was talking with his friend John Flynn and, “he was telling me a story about a fictional character named Chickenbone Slim. I said, ‘What do you mean there’s no Chickenbone? Isn’t there a Chickenbone? Haven’t I heard of a Chickenbone?’ He goes, ‘I couldn’t find one anywhere. You’re Chickenbone now.’”

I ask him how he responds to allegations that his name is anti-Black and he describes a friend of his named Tomcat Pork. “I kind of asked him, ‘What do you think about it?’ And he goes, ‘yeah, it’s part of the persona of blues. It’s not a Black thing, it’s a blues thing.’ And look, if I go out as Larry Teves? Yeah, it’s a great name, I guess. I love Larry, okay? I admit it.” He laughs. “But at the end of the day, who you gonna go see first, Chickenbone Slim or Larry Teves? Especially if you’re going to see blues.”

For Charles Mitchell, creator of the Jus’ Blues Music Foundation, that instinct is perhaps part of the problem. “Most of that audience think that because you go buy a hat and put it on and some sunglasses, now you a bluesman. That’s just those people’s style. That’s just the style of Black folks. That’s what we do, we dress and we’re trendsetters of who we are, we’re not trying to be somebody else.”

Charles Mitchell: “You used to have a guy, Watermelon Slim, who’d wear the green suits when he’d perform, whatever.”

Nico: “That was a white artist?”

Charles Mitchell: “Yeah. You’re not familiar with Watermelon Slim. So you’ve got other people out like that already. He used to be one of the staples at the blues foundation awards back over time and stuff like that.”

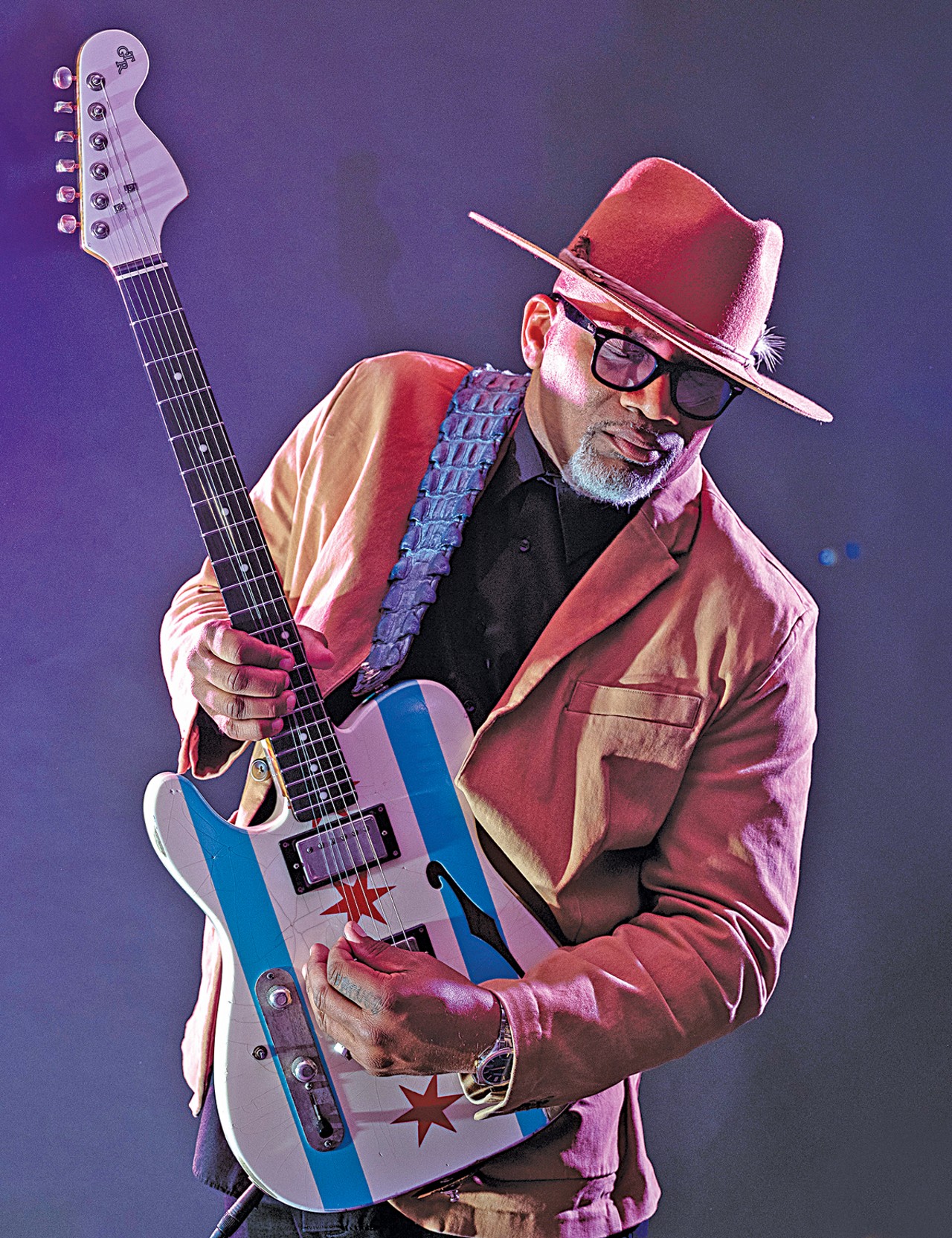

It’s hard not to notice that these accoutrements, that function as signifiers of authenticity for white men, are subject to different encounters for men like Toronzo Cannon.

He shares, “dig this… just Sunday, I got back from Germany. Me and my lady walked into my apartment. I got a guitar and my suitcase and there was a white lady right in front of us. Now I have a nice hat, I have a guitar on my back, and a suitcase struggling to get in the door, and the white lady ahead of me that had just had went into the door pulled the door locked so that I would have to open it myself. Did she see the guitar? Did she see that I was with a lady? Did she see that I had a suitcase, that I could possibly have been coming from a trip? Or did she just see my Black skin?”

He scoffs. “A person with a suitcase and a guitar, a big hat- a bluesman hat- with his girlfriend is gonna rob you? Is that how we disguise ourselves now?”

Nora Jean Wallace recoils when I tell her a version of Toronzo’s story.

“You tell Toronzo he should have called me, I would have came over there and beat her ass. Don’t fool with my baby!”

Nico: It just seems that some white musicians, that they don’t really know these day-to-day experiences that Black people have.

Nora Jean: No, they don’t. They don’t. No, they don’t.

It’s impossible to discuss authenticity anymore without taking a deeper look at where the blues came from. It’s a story that traditionally hails from the Delta, but that aspect of the tale has started coming apart at the seams. I hope you’ll join me for the next installment where we’ll take a closer look at some of the startling scholarship surrounding the birth of the blues.

‘The Black Blues’ is a 4-part series. Here are links to the rest of the series:

Pt. 1: Questions of Authenticity and The Blues

Pt. 3: The True Story of the Blues and The Conspiracy to Cover It Up

Pt. 4: Women-Hatin’ Songs and Black Women in the Blues

Nico this is larrytaylor from Chicago see what iam saying most of the white guys who play the blue name themselves after black peoples who was in slavery or on the slave plantations like the name chicken bone slim names that black peoples had or was given by the slave masters like me Larry Taylor it is not the first name it is the last name Taylor is a white man name given by the last slave owners who had black peoples black bodies as slaves many racist white peoples who want to take credit for what black and brown people did it is a fact that black peoples build America even down to the White House Washington was the first president of America while black bodies were being sold in the back alleys behind the White House it should have been named the peoples house I spent years studying the history of America and other places to what you didn’t know about me I was a black panther in 1969 I was a part of the nation of Kalamazoo from 1972 until 1997 then I became a Sunni Muslim I left in2017 I can say this with a sure fact that black peoples have been done badly every since we have been living here in America what you have to understand there are two America one white and the other is black I agree that America should only be one country so we all can live together in peace as brothers and sisters to believe that is a foolish mistake what do we have the rich over the poor policy’s racist politics did you know that the American constitution doesn’t apply to black and brown people?.just wanted to let you see that I do know slots about this country we live in called America Larry Taylor west side blues ambassador peace and blessings to you and your family.