All interviews for this series were conducted from August 2021 to April 2022.

“Here was among the first blues that I’ve ever heard, happened to be a woman that lived next door to my godmother’s in the Garden District. Her name was Mamie Desdunes. On her right hand, she had her two middle fingers, between her forefingers, cut off, and she played with the three. So she played a blues like this all day long…” —Jelly Roll Morton

There are many versions of the “true” history of the blues. From Ma Rainey’s description of a 1902 encounter with a girl in a small town in Missouri to WC Handy’s hearing “primitive music” from a trio in Mississippi in 1903, tales of where the blues really came from have formed myths of what the real “authentic” is.

As Dr. Adam Gussow describes in Whose Blues?, the Blues Revival movement in the 60s contained strains of a universalist, post-racial philosophy that emerged in response to, “Black bluesism,” a conscious, principled, and angry reclamation of the blues as Black culture in the 60s” spearheaded by the Black Arts Movement.

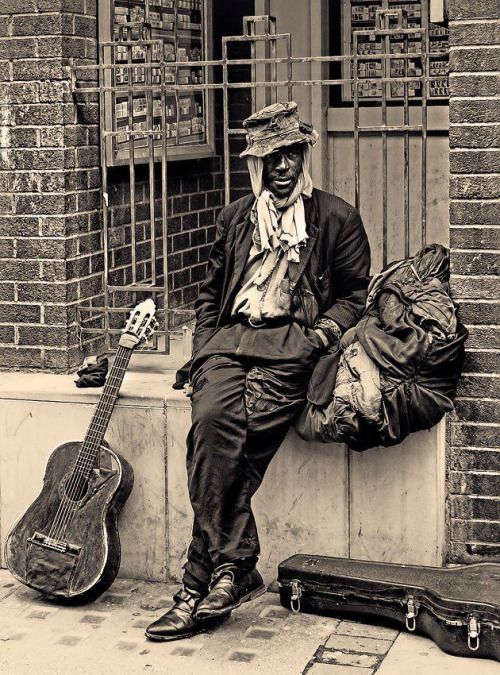

A prototypical bluesman emerged, or, as Christian O’Connell illustrates in The Color of the Blues, was created by people like blues scholars Alan Lomax, Samuel Charter, and Paul Oliver. The historian Marybeth Hamilton describes this figure as a “ragged wanderer…His clothes in rags, his shoes in tatters, his face etched with the sadness of ages: He is the wandering minstrel. In blues revivalists’ hands the central figures of blues iconography, the heart, and soul of the folk tradition.” (Sexuality, Authenticity, and the Making of the Blues Tradition)

To this day, the image of the blues is presented through the lens of this archetype. As Rick Leonard explained when describing a trip to the Blues Foundation in Memphis, “You know when I walked in, I just almost turned around and left. I went in to see the Hall of Fame, and all around the walls were pictures of old shacks. That’s part of the white finish of ‘downtrodden negro’ that the Blues Foundation wants to use.”

Why did this image emerge, and where does it come from? Is it true, or is there another story that’s been hidden?

Chris Thomas King, a blues musician, and scholar who has written a book on the authentic history of the blues says, “the foundations of the downtrodden-blues being connected to slavery, prisons, chain gang workers and things like this that these folklorists and sociologists and music collectors [made]…The foundations of that are in eugenics.”

Cultural eugenics refers to absorbing the cultural creations of subcultures into the dominant culture while erasing the historical material facts of their evolution. These machinations work within American white supremacy to create a basis in culture to justify legal, judicial, and other more sinister actions.

In his book, The Blues: The Authentic Narrative of My Music and Culture, Chris describes the state of the blues as “still constrained by cultural brokers who romanticize the blues as a primitive expression from a primitive people; a mere artifact, not high art.”

I asked him who he meant by cultural brokers.

Chris Thomas King: “The cultural brokers were trained at Harvard…Harvard founded the study of folk music in America and created a folk society there. And then that folk society, Pete Seeger’s father was a folklorist at Harvard, Alan Lomax’s dad studied at Harvard, John Lomax, and so they trained these people. And you’ll find that all this folk eugenics stuff, it emanates out of somewhere around Cambridge, if not Harvard, somewhere else nearby.”

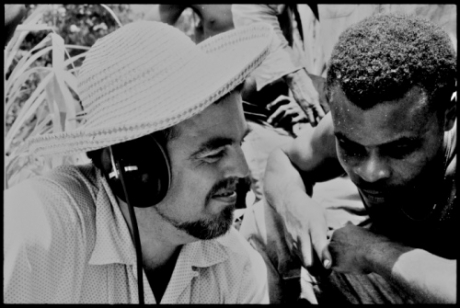

Alan Lomax was an ethnomusicologist who traveled the South collecting Black folk music. He is credited as discovering Leadbelly in a prison, and Muddy Waters on a plantation in Mississippi. In my research, I was struck by a moment in a piece of his called “Sinful” Songs of the Southern Negro, a collection that features Leadbelly. While recording at a prison farm in Mississippi, they force a man named Joe Baker to sing a song at gunpoint so that Lomax can record it (p. 30).

“Late las’ night when I was a-makin my rounds,

Met my woman an’ I blowed her down”

Nico: “Did you feel like Alan Lomax was racist? And that he was involved in a project of intentionally trying to position the blues as being something that it wasn’t?”

Chris Thomas King: “I give a lot of quotes in his own journals and letters that he wrote to people…did he think that white people were supreme and everyone else was subordinate to them and that African and Black African Americans and Black people, in general, were the lowest of the “savage” people? Exactly. That’s exactly what he believed.”

Lomax painted Muddy Waters and others like Bill Broonzy, Memphis Slim, and Sonny Boy Williamson as being the originators of the blues; according to Chris Thomas King, they fit the mold he was looking for.

“Muddy Waters was illiterate—they fit what they wanted the public to think about when they think about Black creativity and Black artistry, that is primitive and savage. If these people are primitive and savage, then their art and their music should represent that.

And if they’re playing clarinets and trumpets and violins, they’re acting white. You know, because, ‘we’re the civilized people and they are not authentically Black anymore.’ They had this twisted eugenic criteria for who they would even put a microphone in front of.”

Nico: “And this project…is coming from essentially a type of eugenicist knowledge production that has its origin around Cambridge and Harvard?”

Chris Thomas King: “That’s exactly what I’m saying. When Dorothy Scarborough is coming down to these places and they’re looking for slave melodies and things that they want to create as being Black folk culture, they didn’t speak to any Black people. They didn’t convene with any African professors or African people, and say well what is African folk music, how would you define it? No Black people were involved, no Black women were involved.”

The irony is that it would be in part due to the work of Alan Lomax that the authentic story of the blues would begin to come to light. In 1938, Lomax spent hours recording Jelly Roll Morton, a Black Creole man from New Orleans who had lived there during the birth of the blues.

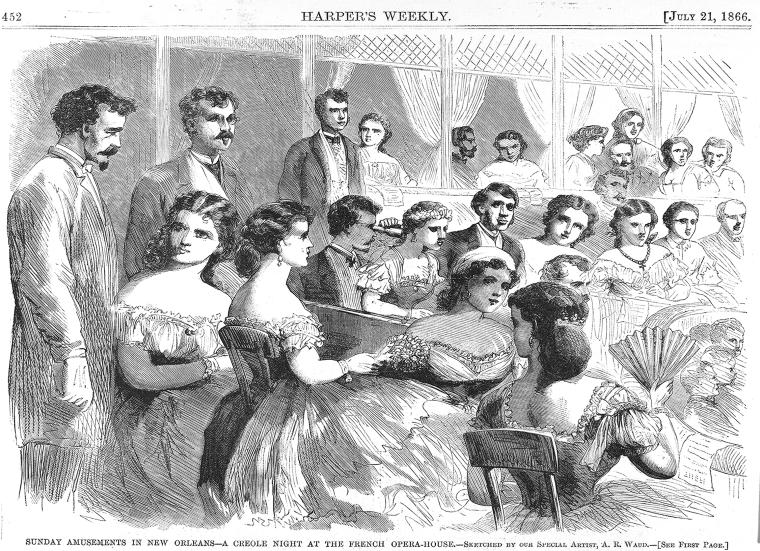

As I learned from Chris Thomas King, when the Spanish controlled Louisiana, they called Black Africans who were born there, Creole. When America bought Louisiana and began to install their Anglo values, they were trying to do so in a place where free Black people had lived since the 1700s, more than any other part of the country. Black Creoles were “fighting for their way of life that was being annexed.”

Chris explains that for the French-speaking Black Creoles, music was a dominant part of the culture. “Music was a part of life, part of funerary things, celebrations, balls… 100-piece Black orchestra that was supported by free Black people. And they had their own theater, a renaissance theater in the 1830s, 40s, and 50s, up until the Civil War.

And so there was a long history of music and clarinets and trumpets and things like this from the orchestrations and opera houses of Black Oprey houses during antebellum times when there were no Black people in what we call Northern MI, the Mississippi Delta.”

Chris tells me New Orleans had a “history of music that dates back to the late 1700s at least,” while “there were never any Black slaves in what we call the Missippi Delta. There’s no slave shacks, you can dig in the ground and you won’t find any pottery. there was no Black people there, it never happened.”

Chris Thomas King: “Our culture developed different. The drum was never banned in New Orleans. We’re totally different, we didn’t come to America in the same way, and we have a whole different unique experience because we weren’t even part of America until 1803. That’s when America bought Louisiana but it wasn’t until 1818 that Louisiana became officially America and people spoke French in the French quarter until the 1930s.”

When Black Creoles like King Oliver, Jelly Roll Morton, and Mamie Desdunes began forming small seven to eight-piece ensembles, Chris describes them doing so in favor of “a minimalist art movement that broke away from the opera house, the theater and all that, and became more nimble.”

Even the word blues comes from the Black Creoles. “Sacré bleus, the creolization of the word sacre bleus.” It was a “defiant philosophy,” Chris says, that took “anything that Anglo or America held sacred, like the Christian hymn, ‘When the Saints Go Marching In,’” and “Creolized it, and made it your own.”

Jelly Roll Morton, a Black Creole pianist born in New Orleans in 1890, didn’t claim to have created the blues, as he painted an image of an art form emerging from, as Dr. Gussow says, “brothel piano players…it was music that people might have wanted to listen to when they were getting ready to go upstairs with somebody.”

Jelly Roll is very clear on the first time he heard the blues, “…a woman…her name was Mamie Desdunes.” Chris Thomas King notes, “As for singing and composing, she’s the earliest composer that Jelly Roll said that he knew.”

Music was an important part of the tradition of Storyville, where even the pimps played piano. “The reason many of them were pianists was because whenever they were down on their luck, they could always get a job and be close to their girls–play while the girls worked…” (A Bad Woman Feeling Good: Blues and the Women Who Sing Them, Buzzy Johnson)

Good piano players made a killing playing these spots and Mamie Desdunes was no different. “When Hattie Rogers or Lulu White would put it out that Mamie was going to be singing at her place, the white men would turn out in bunches and them whores would clean up.” (Marybeth Hamilton, Sexuality, Authenticity, and The Making of the Blues Tradition)

Mamie Desdunes was the daughter of Rudolph Desdunes, who wrote the first history of Black Creoles in Louisiana and was a first-generation Black Creole whose family migrated from Haiti. According to Chris Thomas King, Rudolph “was central in shaping and organizing a committee to fight Jim Crow” and when it comes to “[blues] philosophy, people should know more about him.”

On the Lomax recordings, Jelly Roll goes on to describe the best piano player he knew, a queer Black man named Tony Jackson.

Jelly Roll Morton: “Tony Jackson was the favorite. And he was the favorite amongst all. His range on the blues tune would be exactly like a blues singer, on an opera tune just exactly like an opera singer. He went to Chicago and was the favorite there. He was very much instrumental in me going to Chicago.

“[He] liked the freedom that was there. Tony happened to be one of these gentlemen that’s called, a lot of people call them a lady or a sissy or something like that. But he was very good and very much admired.”

Alan Lomax: “Well was he, was he a fairy?”

Jelly Roll Morton: “It’s either fairy or steamboat. A fairy I guess, That’s what you pay a nickel for I guess.”

This version of the blues’ origin is vibrant and provocative, but as Marybeth Hamilton says, “Situating the blues in a nexus of sex, commerce, and urbanism, Morton’s story carries all the wrong resonances…” Blues chroniclers prefer to envision blues as “a music of masculine melancholy, sung by drifters and detached from any commercial base.” (Sexuality, Authenticity, and the Making of the Blues Tradition)

Chris Thomas King: “Alan Lomax who had all this information recorded…he hid it…but he went on to write books like Land Where The Blues Began.”

Nico: “All about the Delta.”

Chris Thomas King: “Yeah, all that eugenic bullshit. They couldn’t allow Jelly Roll to be the face of the blues. It’s the same reason why Black people didn’t build the pyramids. Of course, that wasn’t Black people, they were from Greenland, or they were Russians, they could have been Martians…but their skin wasn’t Black because Black people are savages.”

Alan Lomax chose not to release the Jelly Roll Morton recordings during his lifetime, which likely altered the path of history. The recordings only became available through the Library of Congress in 2002, after his death.

As I’m writing this piece, my Great Aunt Fannie is in hospice. She’s the last person in my family who actually lived on the land my family once owned in Louisiana, where the Black Creole side of my family had a plantation. The KKK forced us off our land, and that’s when Aunt Fannie, the youngest child in a large family, moved with her brother, my grandfather, to Oakland, California. My grandfather tried unsuccessfully to win the land back in court.

Our story is just one in a long history of the destruction and replacement of people in America, but despite everything, we’re still here.

I hope you’ll join me in the next part of this series, which will look a little more closely at women and queerness in the blues.

‘The Black Blues’ is a 4-part series. Here are links to the rest of the series:

Pt. 1: Questions of Authenticity and The Blues

Pt. 2: Authenticity, Chickenbone, and Blackness

Pt. 4: Women-Hatin’ Songs and Black Women in the Blues