All interviews for this piece were conducted from September to December of 2021.

In America, misogyny is the rule and exceptions are rare. When we talk, it’s Toronzo Cannon who points out that there are women who might be “uncomfortable by constantly hearing that they are no good in blues songs,” and observes that many women might even become desensitized to the prevalence of what he calls “my woman left me” blues.

Toronzo: “I try not to write what Gatemouth Brown calls women-hatin’ songs. Because women don’t mess up all the time…there’s some men out there, believe me, messin’ up good.”

Gatemouth Brown performs “I Hate These Doggone Blues”

I’m struck by the term women-hatin’ songs, so I asked a few women blues singers if they’d heard it. None of the women blues singers I spoke with had heard the term “women-hatin’ songs” and didn’t seem to have observed much lyrical misogyny. In fact, some staunchly denied their existence, such as Ivy Ford who said, “I don’t think I’ve ever heard a song that was really racy or raunchy with a woman being the subject of, or being demeaned or less than.”

Still, observations about blues-misogyny are fairly common. As Sharon Lewis described in a Blues Symposium on race and gender in 2012.

“We don’t all sing about them, ‘(dum dum dum do dum—bass blues riff) I’m gonna grab my woman (dum dum do) knock her down, drag her by the-’ it’s not that.”

Jim O’Neal, co-founder of Living Blues magazine, was speaking at the Blues Foundation’s 2019 panel on Blues and Race when he passed on a piece of aural history learned from Willie Ting, who had learned it from an elder, suggesting that often when men were singing about a woman mistreating them, they were really talking about white bossmen. “But you couldn’t come out and say those kinds of things explicitly back then, you might get lynched.”

People were lynched for less, such as a man who is lynched by a mob of 50-60 “on account of protecting his own [pregnant] wife because he didn’t want his wife to work out on the plantation.” (Land Where The Blues Began)

Big Bill Broonzy said a man named Andrew Belcher was killed in 1913 for marrying a Black girl that a white man wanted to date. “They” then killed her and her father, “then they went and killed his daddy and they killed his mother and then one of his brothers, he went out to fight, to try to protect them, and they killed him so they killed twelve in that one family.

“…They got a girl in the family that they like, you just want to let him have her, because if you don’t he’ll be liable to do something, you know, s’ outrageous, because when they see a Negro woman they like, they gonna have her if they want her.”

In early collections of blues songs by folklorists like Howard Odum and Alan Lomax, one finds a fair amount of those “women-hatin’ songs.” One writer compares women to dollars passing “from han’ to han’ Jes’ de way dese wimmen goes from man to man.” (Sinful Songs of the Southern Negro) Another man says,

Well, I would not marry Black gal

Tell you de reason why

Ev’y time she comb her head

She make dem goo-goo eyes

Well, she roll dem two white eyes

But in taking a close look at early blues lyrics, there are arguably equal instances of love towards women. One man remarks, “The reason I loves my baby so / Cause when she gets five dollars she gives me fo’.” Another man thinks of his lover as he hears the train whistle, “I believe my woman’s on that train / O babe! I b’lieve my woman’s on that train. She comin’ back from sweet ole Alabam’ / She comin’ to see her lovin’ man.” (Notes on Negro Music) A different man displays admirable boundaries:

There’s a girl I love, she don’t pay me no mind

There’s a girl I love, one I bears in mind

She’s a merry girl, but I love her jus’ the same.

(Odum, Folk Song and Folk Poetry as Found in the Secular Songs of the Southern Negroes)

No doubt there’s also a natural question raised about the curation of these works. I’m curious how many nonviolent songs were passed over by these collectors. These are curators whose work is punctuated by moments of stark white supremacy, such as when Odum explains, “the negro is often a coward, and loves to boast of things he is going to do,” (Folk-Song and Folk-Poetry as Found in the Secular Songs of the Southern Negroes) or when Charles Peabody introduces a collection with the language of a nature documentary that reads as almost a parody:

“At times we had some opportunity of observing the Negroes and their ways at close range.” Later Peabody describes a song as, “[giving] splendid insight into negro characteristics in the role of the clown, who has mixed his thoughts, wits, bits of song and burlesque, with the crude jokes he has heard.” (Notes on Negro Music)

There are almost no songs by women in these early collections, and across blues scholarship, Dr. Adam Gussow notes pervasive sexism. “The way the blues story is told, people forget that the first blues stars were the women. That in fact that when people used the word ‘blues’ for the first time they actually meant the women.”

Angela Davis explains in her monumental book Blues Legacies and Black Feminism, “Initially the professional performers of this music—the most widely heard individual purveyors of the blues—were women.” Blues stars like Bessie Smith, who “earned the title ‘Empress of the Blues’ through 750,000 sales on her first record,” wrote songs that

“affirmed working-class Black women’s sense of themselves as relatively emancipated, if not from marriage itself, then at least from some of its most confining ideological constraints…The female figures evoked in women’s blues are independent women free of the domestic orthodoxy of the prevailing representations of womanhood through which female subjects of the era were constructed.”

As Bessie Smith wrote in “Young Woman’s Blues,” she had “No time to marry, no time to settle down/ I’m a young woman and ain’t done runnin’ ‘round.”

Ivy Ford describes some of these early songs. “We think some of the rap music these days is raunchy, if you listen to some of the lyrics back then on them race records, hooo-hooo. And it was women that was singing them.”

But within the writing of blues history, according to Dr. Gussow, blues women were seen as less authentic, “for two reasons. Number one because they were in theatrical settings, so the theatricality was seen as somehow delegitimizing.” The second reason is that many of the songs they sang were written by men.

Dr. Adam Gussow: “So they sort of wrote the women out of the emergence of the blues. And so Dinah Washington, for example, who’s like a blues queen, she’s a latter-day blues queen, except the generation after the Bessie Smiths and Ma Raineys. She gets kind of written out, Elijah Wald is pretty good about bringing her back in, but she’s as big in her own way as BB King but your standard blues history would never configure her that way.”

Today in the professional blues scene, some feel there is a real sense of women being at a disadvantage. As Nora Jean Wallace remarked, “A woman that do blues, they take advantage of her.” And Ivy Ford said, “I totally get there are some job opportunities, there are some different opportunities that a woman or performer will get looked over, just for the sake that she’s a girl. It’s not that obvious always, but it’s there.”

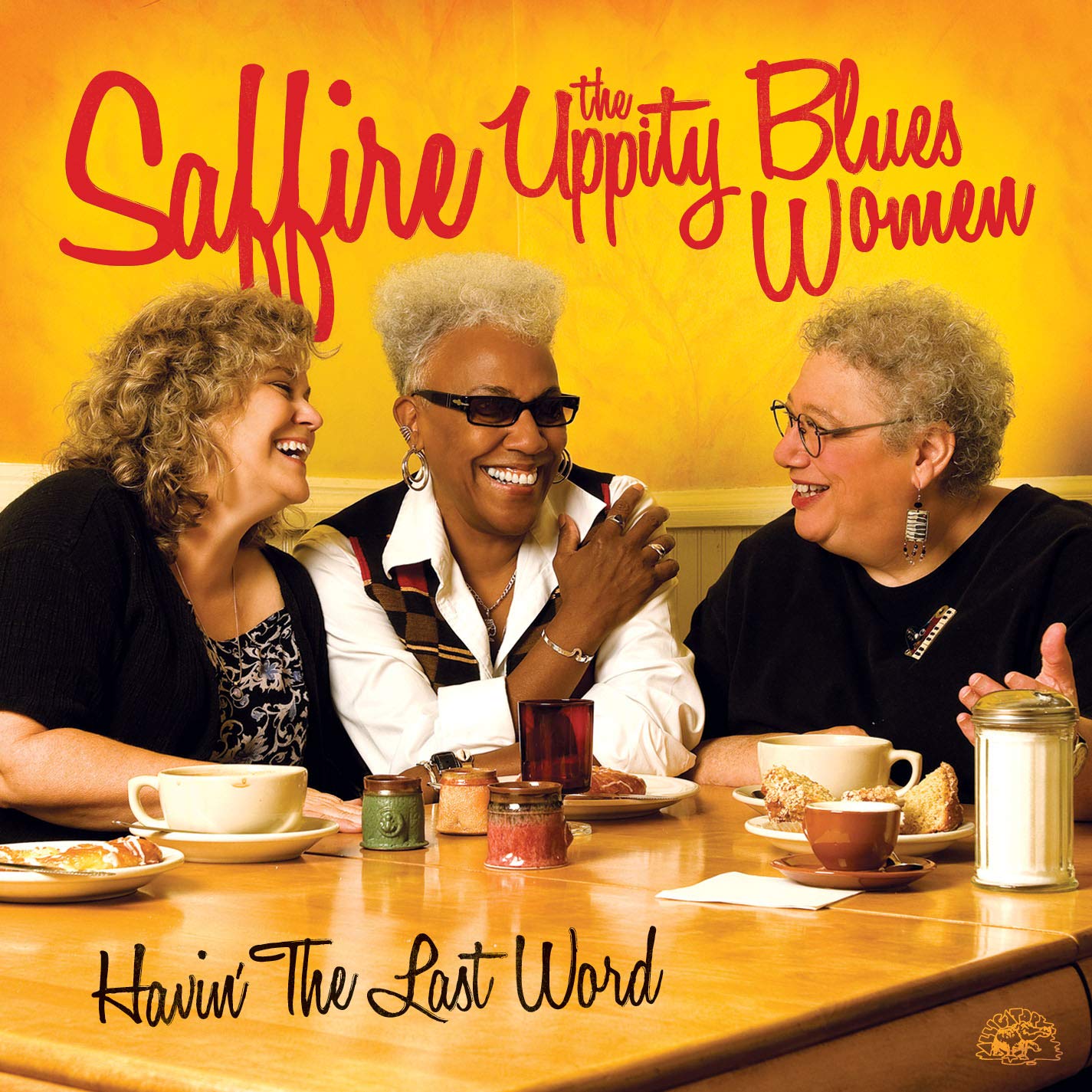

Still, there are those whose experience is different, such as Gaye Adegbolola.

Nico: “So do you feel like women and men have the same opportunities in blues?”

Gaye Adegbolola: “From that panel I took part of in January of 2020, it sounds like they don’t. But the things that I was hearing, as a Black woman, we have so many more things to fight about. You know, it was about not having the right entrance into the studio, not being accepted with the musical knowledge and stuff like that. But I didn’t have that problem, we [Saffire – The Uppity Blues Women] didn’t have that problem.”

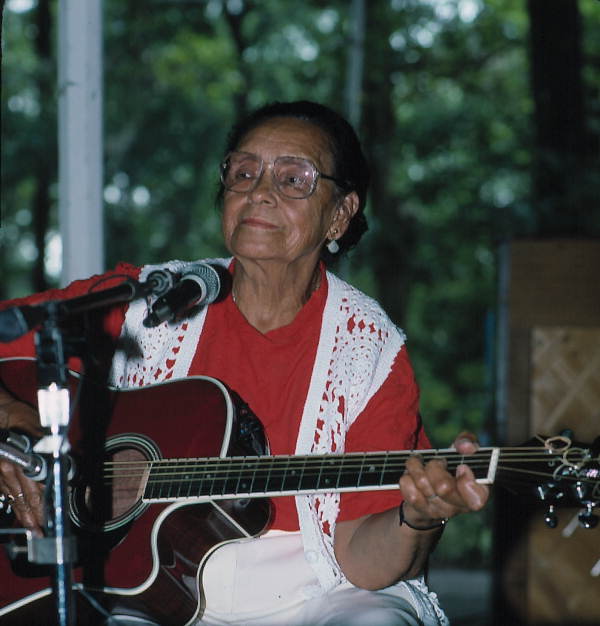

The fact does stand that fewer women, especially Black women, are signed to blues labels. For Gaye, that came down to raising a family.

“I think that for the most part if you’re gonna be on a label, if you’re talking about a label, you’re gonna have to travel. And a lot of women can’t travel. A lot of women got children, a lot of women have to pay the bills, so that’s what has happened. I mean you can go back to somebody like Miss Etta Baker, who is a phenomenal Piedmont-style guitar player, and, you know, she couldn’t go on the road because she had a family.”

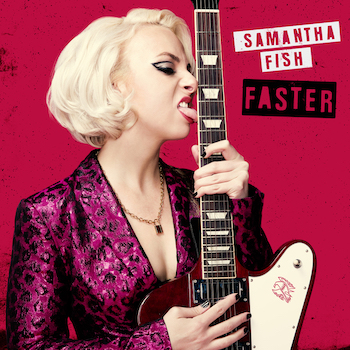

Some raised the issue of white women replacing Black women within the blues. One source, whose identity is being withheld due to the nature of their work, said, “we’ve got a whole host of young white women who are dominating festival circuits, from Ana Popovitch to Samantha Fish to all kinds of regional young women who are being marketed as these sort of sexy young things that are playing electric guitar and singing blues music.”

She also notes that in the “late 70s through early 90s there was a huge amount of Black women blues singers in Chicago, and I mean just a couple of dozen of these women that sort of dominated the scene back then, but nobody recorded them.”

This silencing of Black women, original purveyors, and creators of the blues is exemplified by the legal actions of Lady Antebellum. Many have probably heard about the Lady Antebellum controversy, but if you haven’t, Lady Antebellum is a white band that decided to change their name in the wake of the George Floyd Protests.

They shortened it to Lady A, then sued the Black woman who had performed as Lady A for almost 30 years as a blues singer, claiming she had never registered the name with a trademark. They settled the lawsuit earlier this year, but details are not public.

Regardless of the terms of their settlement, if you search “Lady A” on Google today, you won’t find an Anita White listing unless you scroll halfway down the page. Her face appears once in the image results at the top, squashed in the middle of the white musicians who took her name in honor of Black lives.

While the story of the blues redounds with pioneering Black women from Mamie Desdunes to Bessie Smith, Ma Rainey to Dinah Washington, much of that history is only now being told through revisionist scholarship by people such as Paige McGinley. Without Black women, it’s safe to say there wouldn’t be blues music, but the legacy of their erasure marches on.

I hope you’ll join me for part four where we will look at power structures in the blues.

‘The Black Blues’ is a 4-part series. Here are links to the rest of the series:

Pt. 1: Questions of Authenticity and The Blues

Pt. 2: Authenticity, Chickenbone, and Blackness

Pt. 3: The True Story of the Blues and The Conspiracy to Cover It Up