All interviews for this piece were conducted from September to December of 2021

I was introduced to the blues by a member of one of the most storied musical families in America—the Eubanks.

As a fledgling Oberlin Conservatory music nerd with a classical music background, I’d tried to play a little jazz but still didn’t know how to read charts despite sight-reading classical notation well. It was one of those chance encounters, a riff the universe plods into your life on days like Cinco de Mayo, when everything changed; Robin Eubanks and I drunkenly stumbled into each other at Agave Grill, me giggling and spewing words like a gas hose, him with the calm, cool-as-fuck collectedness of a professional bass player. By the end of the night he’d asked me to work with him and the following fall I began private study.

Robin gave me blues songs to transcribe, and built-in me a sturdy reverence for Bud Powell, who had inspired Bird and would have conquered the world if he hadn’t had a couple of screws knocked loose by the cops after a gig one night. Powell, like many Black intelligentsia of the mid-twentieth century, escaped to France, where he died too young.

I begged Robin to show me how to play jazz, but he insisted we were starting where we needed to, “The blues is jazz.” He’d say, stuffing the gram of weed I’d brought him into his shoe, “Learn these solos, man.”

Over a decade later, I’m in Chicago, playing with a band, and playing blues. I’m learning standards when I get the idea for a new piece. I’m curious about the, well, maleness and whiteness of the blues I’d observed from afar. How do blues musicians think about appropriation? So I started booking interviews.

I asked Dave Specter, a professional blues and jazz guitarist on Delmark Records who wrote a song called “The Ballad of George Floyd,” what inspired him.

“The police brutality. The history of that in our country… the rare thing about the George Floyd incident is it was caught on tape for all of us to see. And I’m sick of it. I’m sick of it. So I wrote a song about it.”

Nico: “You said I think we need to move beyond the divisions of race and realize it’s music, and the blues is universal. What did you mean by that?”

Dave: “Well, um… just what I said, it’s pretty, I, y’know, I don’t think music should be looked at based on the color of someone’s skin. If you’re a dedicated blues musician, you’re playing Black music that’s invented by Black people, but it is now a universal art form and can be and should be played well by everyone.”

I hear the ghosts of the Black Arts Revival Movement in my ear. Are you a part of a tradition of white men supplanting Black thinkers and performers in the pursuit of universalism?

I ask Dave if he feels like he’s appropriating Black music when he plays the blues and he’s very careful with his language: “I find that type of argument to be one that is shared among pseudo-intellectuals that aren’t musicians and aren’t artists. Like I said earlier, I give due credit to the Black artists and musicians that invented this music… but it’s become an art form, it’s become a musical genre. It’s not called Black blues music.”

I’m curious if he feels like he’s benefitted in his career by being white.

“Benefitted? In terms of my career? No. I mean I think I would be doing the same thing if I was Black and I’d probably be at a similar point in my career. I don’t think about it in terms of color. No. I mean, I think, in terms of like my level of success, is that what you mean? Benefitted? I would say, probably not. And I would probably say that if I were Black and playing at the level I am now, I might even be more successful.”

Dave explains that since the field is, “dominated by white musicians,” he might have an advantage being one of the few Black ones. I ask him if he thinks the blues being dominated by white folks is a product of racism and he says it’s not, “I think it’s more a product of tastes.” Black people became more interested in hip hop and jazz and funk after the ‘40s, ‘50s, and ‘60s, while “a lot of white people are catching on to it and stick with it.”

A couple of the musicians I interviewed had heard the idea that being Black might be a benefit in the blues before. Ivy Ford, Chicago-based guitarist and singer, said, “I’ve met some other musicians, both like big Chicago and local white guys, white chicks stuff like that… and they might more frivolously be like, ‘oh yeah, but if I was Black it would be a lot easier.’ No, no, just because you’re Black don’t make the fuckin’ thing. you know?”

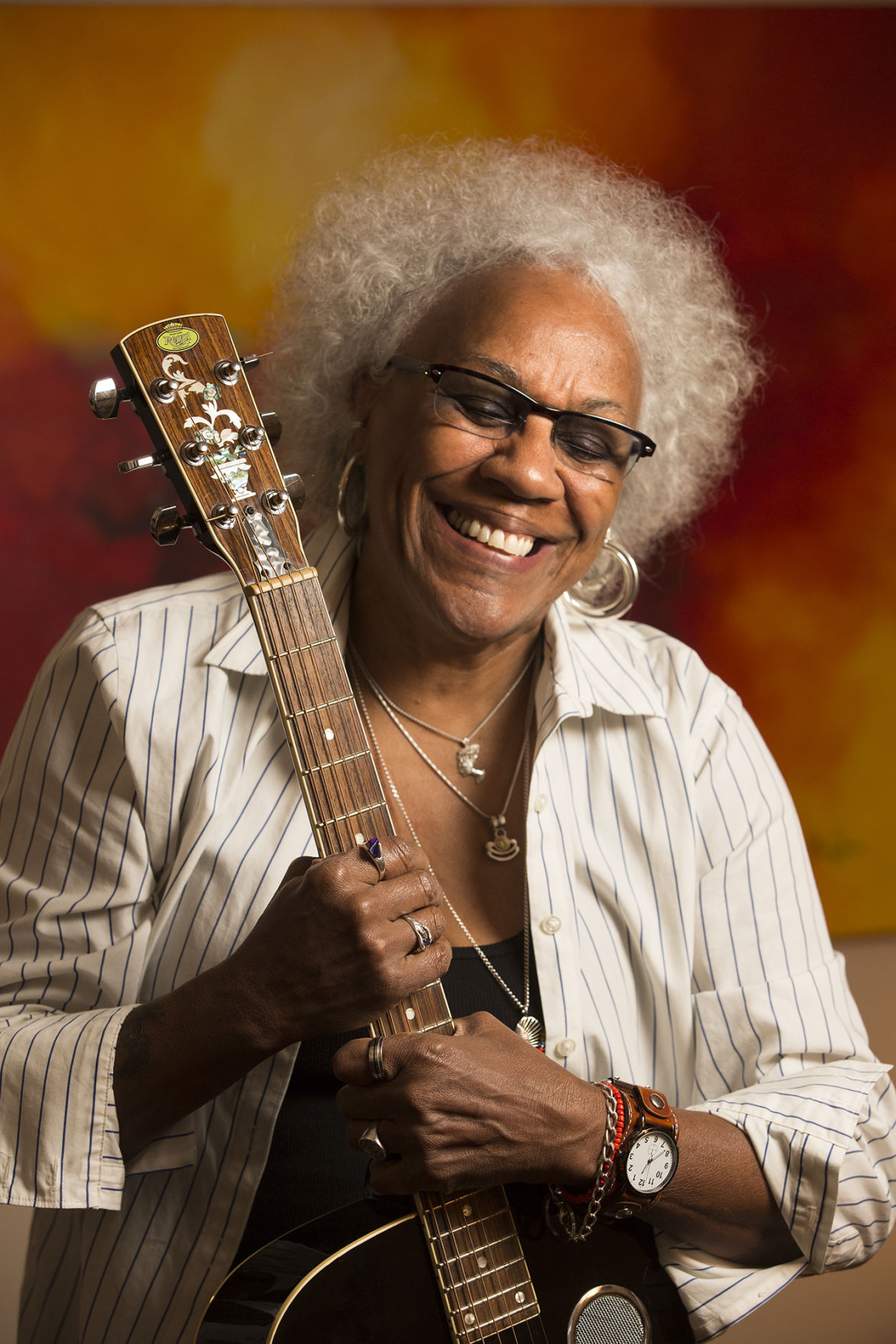

Gaye Adegbolola, who was a member of Saffire: The Uppity Blues Women, and now performs independently had a bandmate who, “felt that she would have had more acceptance if she was Black.” But Gaye points out, “that’s the tradeoff.”

One source becomes audibly angry when I ask her about Dave’s comments. First pointing out that Dave Specter comes from a “wealthy family” with a “very, very high powered background,” she adds, “he also went to high school with the guys that ran Delmark records. And he was a stock boy at Delmark records for a couple of years before he got a record contract with them after just learning to play the guitar… for him to not understand that that’s all part of the question that you asked, shows a huge lack of sophistication and a huge lack of sensitivity to his position and how he got to be where he is.”

This person was granted anonymity due to the nature of her professional work and fear of never working again at Space, a prominent blues venue in Evanston, which Dave co-owns.

Toronzo Cannon of Alligator Records seems to think his Blackness is a double-edged sword. Having been a full-time CTA driver in Chicago for much of his career, he’s conscious of how his image has been colored.

“In some ways, yeah, and some ways, no. Because I might get more credibility ‘cus I’m Black, because, ‘oh my god, you’ve worked in the ghettos, Toronzo. You had to work.’ Because a lot of people, they would say—you traveled the world and you still have to work a job? Yeah. yeah. That’s what I do.”

On the other hand, he points out how artists like Stevie Ray Vaughan seem to indicate other inclinations.

“Maybe him being from Texas and being a white guy playing the way he played, and playing Black blues or whatever you wanna call it. I think it feels better to society to see someone [white] playing Black blues.”

Toronzo gives the example of Sun Studios, Elvis’ original studio, “The guy who owned Sun Studio said, ‘If I could find a white guy to dance like a negro, I’ll make a million dollars.’ And that’s what he did. Found Elvis. So much so, where Elvis was being banned from TV stations, they only showed him from the hips up ‘cus they didn’t want him to dance like Black folks had been dancing for years. And all of a sudden Elvis is the king of rock and roll. What happened to Chuck Berry, and Little Richard, and Fats Domino?”

Harmonica player and Blues Hall of Famer, Billy Branch, pointed out “the highest-paid performers in the blues industry are not Black performers,”

“What we experience now is that there are blues festivals without any Black artists on them. Which sounds like an oxymoron, because again, Black African Americans were the inventors and creators. It’d be like, suppose Black people gave a Celtic festival with nothing but Black people, how would the Irish people feel?”

When I speak with Charles Mitchell, director of the Jus’ Blues Festival, which is dedicated to “preserving Blues heritage” and recognizing Black artists “left out of the more popular mainstream media and awards shows, he laughs at Dave’s comments,

“Well, look at the Black ones who are not, how ‘bout that? What would make them, if they were Black, what would make them more successful than the ones that are Black and aren’t successful? I’m gonna name some more artists like Otis Rush, Sun Seales… and I’m naming artists right now that people don’t really know these artists outside Chicago and overseas somewhere.”

Blues scholar and professor of English and Southern Studies at University of Mississippi, Adam Gussow, takes a more circumspect approach to the question:

“I know from an essay that I helped publish that consists of a long interview with the premiere Japanese-born piano player who’s in Billy Branch’s band, he talks a lot about the sort of problematic racial dynamics that make it tricky for an Asian man. In some cases being left out of band photos, for example, when Chicago bands travel to Europe.

So there are ways in which you could say, I don’t even wanna call them racist ideas, purveyed by promoters and club owners, might rebound in some cases against a guy like Dave Specter and the evidence is there that this happens. It shows up in Dave Grazian’s book, Blue Chicago, that there is a kind of racial inversion in the Chicago blues scene, where you have owners of clubs most of whom probably are not Black, saying, look, what the tourists want is they want a Black band. And you gotta have not only a Black leader but I’d prefer an all-Black band.”

After accounting for that, he takes a big sigh and laughs, “But you know, yeah, there’s evidence that I offer to the other extreme, in my book [Whose Blues: Facing Up to Race and the Future of the Music] when I’m examining players like Billy Branch and Sugar Blue and the kind of gigs that white harp guys are getting who aren’t as good as Billy and Sugar, but are getting big festival gigs.”

Scott Fitzke, current Board Chair of the Blues Foundation, has more to add about the disparities: “If you look at statistics and you look at the number of Black artists that are performing at festivals and booked in clubs, I think that there’s issues with parity. I don’t wanna impute racism to anybody, we don’t wanna say all concert promoters that don’t feature African American musicians are racist without looking at each individual situation, but when you look at the numbers it’s definitely of concern to us that it’s African American music and we’d like to see the artists that are carrying that tradition on, the African American artists, get their fair shake.”

Dave and I spoke again after this piece was released and he told me the anonymous source’s comments were “absurd and false.” Dave says he “grew up in a middle-class neighborhood” just north of Albany Park in Chicago. He denies going to high school with anyone from Delmark Records, though he was “acquaintances” with the “manager at Delmark records, Steve Wagner,” who grew up in the same neighborhood and, “helped me get the job as a shipping clerk [at Delmark].”

Though he denies being from a “high-powered family,” I ask him about a rumor that he’s related to Chicago critic Gene Siskel and he acknowledges Gene was first cousins with his mother.

After describing a litany of Black musicians he’d worked with who were “surprised” and “flattered that people like myself and Nick Moss wanted to learn his music and play in his band,” he tells me, “I just know from my experience, and I dedicated my life to this music starting in 1985, I just have seen very little tension, racial issues amongst musicians.”

He says, “the only time I’ve ever felt any tension with race are with white club owners,” and describes a white club owner who once told him, “Dave, first of all, you’re white. Second of all, your singer tries to imitate B.B. King and he’s Black.”

While Dave acknowledges the problem addressed by Billy Branch about prominent festivals without Black performers, “I think that’s wrong,” He makes it clear that “It’s about the music…it’s not about the color of one’s skin, it’s about how you play, how you respect the art form, how you present it and that’s the bottom line for me as a musician.”

It became clear to me that the blues is a cultural space where a battle is being fought.

At stake is an identity ground out in the millstone of the United States, leavened in the Delta; an identity that challenges what the South really is, and asks provocative questions about sexuality, race, and authenticity.

I spoke with musicians including blues musicians like Lil Ed Williams, Billy Branch, Nora Jean Wallace, Ivy Ford, Toronzo Cannon, and more. I spent months researching the origins of the blues and modern and classical scholarship. Over the next few weeks, I’ll be releasing pieces that explore queerness, power, origin, and race in the blues.

I hope you’ll join me for the next installment, and I hope that by the end of this series you’ll have a much better understanding of the blues in America.

‘The Black Blues’ is a 4-part series. Here are links to the rest of the series:

Pt. 2: Authenticity, Chickenbone, and Blackness

Pt. 3: The True Story of the Blues and The Conspiracy to Cover It Up

Pt. 4: Women-Hatin’ Songs and Black Women in the Blues

This piece has been updated with additional comments from David Specter.

Great article that was balanced and well-written. Thank you for being a literate music nerd. I look forward to the next installment.

Nice read. Pulling back the layers of fear of reprisals to get an honest opinion from some Blues artists can be challenging.

You might want to look up Chris Thomas King,for an interview, I played for his Dad,Tabby,ShoNuff

I wanted to respond to the comment from Gaye Adegbalola where she claims I’m from a very wealthy family with a high powered background. This is flat out false and frankly absurd. My father sold insurance and was a community organizer in the middle class, northwest side neighborhood of Hollywood Park. My mother worked at Northeastern Illinois University in their University Relations Dept. They lived in a small house for over 35 years that they paid just over $30,000 for.

There is/was nobody high powered in my household.”

And as a musician who was mentored and hired by legendary bluesmen like Hubert Sumlin, Sam Lay, Son Seals and Jimmy Johnson, the issue of race never once came up. It was all, and always about playing the music we love: the blues.

My apologies to Gaye. I now see it was the brave anonymous source who made up the above mentioned stories about my family and my past. I also did not “go to high school with the guy that ran Delmark Records”

Nico: next time consider checking facts before publishing fiction like that.

The question is, how do you, “give due credit to the Black artists and musicians that invented this music”? The saying, “No Black, No White, Just Blues”, doesn’t give credit to the origins of the music, yet I have to single out the Blues Foundation in particular by profiting from this lie. White bands for the north travel to Memphis for a “blues competition”, and all they bring back is this slogan, which allows them to ignore the history the music and human relations in America. When white artists and festival producers go onstage and denounce this slogan (Adam Gussow has done it), then I’ll give them credit.

How do I give due credit to the musicians that invented the music? Here are a few ways:

I record and produce recordings covering the originators’ music, always giving them proper credit, as well as praising their artistry both onstage and in interviews worldwide.

I record and produce collaborative recordings with contemporary artists, from Otis Clay to Jimmy Johnson, Billy Branch to Jesse Fortune, Jack McDuff to Jimmy Johnson.

I also spread the good word about their contributions on my podcast, heard in over 60 countries, with interviews including Billy Boy Arnold, Sam Lay, Jimmy Burns, Shemekia Copeland, Katherine Davis, Jimmy Johnson, Mud Morganfield and many more. These interviews tell the artist’s stories – in their own words.

I also write and record protest songs and videos about racial injustice including The Ballad of George Floyd featuring Billy Branch, which caught the ear and attention of Dr. Cornel West.

Dave Specter has dedicated his career to blues music and continues to help and promote black artists as he always has for over 3 decades. As a musician and as a teacher he passes on the blues tradition he learned directly from giants like Son Seals to younger artists wanting to learn about blues music. And what a shame that the anonymous source flat out lied about him and his family.

In response to the numerous lies by the “anonymous” source who slandered me.

Let me state some facts about my career. I did NOT “go to high school with the guy that ran Delmark Records”. I was NOT “a stock boy at Delmark records for a couple of years before he got a record contract with them after just learning to play the guitar. I signed with Delmark after playing guitar for 11 years, and spent 5 of those years playing and apprenticing with bluesmen and women like Sam Lay, Hubert Sumlin, Steve Freund, Jimmy Johnson, Jimmy Rogers, Willie “Big Eyes” Smith, Calvin “Fuzz” Jones, John Littlejohn, Big Time Sarah and Son Seals. All of these artists hired me to be part of their bands and welcomed/encouraged me to learn their music. If that’s appropriation then I question your motives. I also question why the author of the article would not check his facts before printing quotes from such BS “anonymous” sources. And If you think I’m “from a very, very wealthy and powerful family”, I’ve got a membership in the flat earth society I’d like to sell you.